-

Quote of the day – from me

Rationalism is a force multiplier, not a force

The same applies to most philosophy

-

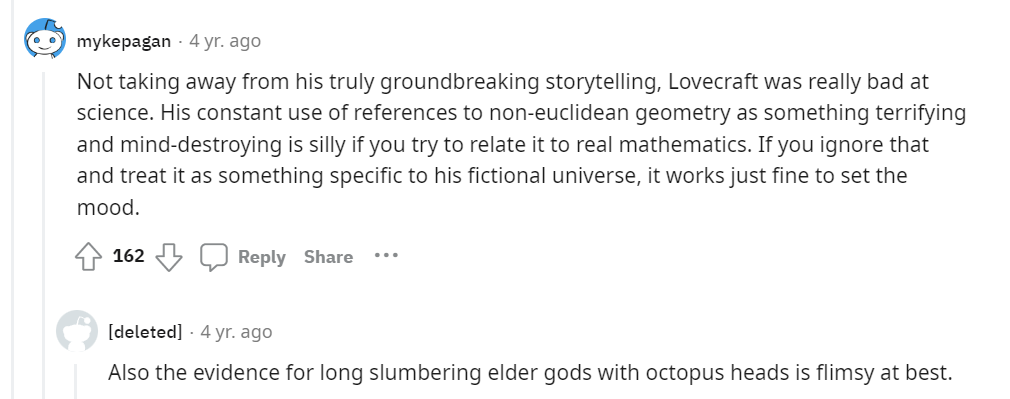

Gems from Reddit on HP Lovecraft

-

Quote of the Day from CS Lewis

I’ve probably posted this before, but

Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.

-

Would anyone come to a Progress Studies Atlanta group?

A while back I had the thought that Progress Studies would would take the place of Effective Altruism after the PR and financial hit of the FTX implosion – that seems not to be happening. I also had the thought that I should create a “Progress Studies Atlanta” group, but I’m not sure where to begin on that. The obvious answer is “Something, something Georgia Tech” but I have no connections there.

Ideally it would be a monthly gathering of technical experts or technical experts talking and letting information rain like manna from heaven to experts in other fields, a la a classic salon or the Lunar Society.

If you have any thoughts please leave them in the comments or contact me directly.

-

Alms for Oblivion by Peter Kemp

From my Notion book template

The Book in 3 Sentences

- Alms for Oblivion is the final book in Peter Kemp’s war memoirs. It covers his time in the far east (Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia) slightly before and after the surrender of Japan. He spends much of his time trying to prop up the French and Dutch colonial empires, often using Japanese troops who had not yet been released from their army service.

Impressions

It was the best written of his books, it had to most geographical information of any of them. I did spend a lot of time pondering how much of his impressions of the local population were true vs a heavily biased British viewpoint. I was the most surprised by the lack of self reflection of how he went from law student to Lt Colonel in charge of a (sort of) country in a very short period of time. The post war colonial world was also very, very fractured, more so than I would have thought

How I Discovered It

I read the previous two books in the war trilogy

Who Should Read It?

Anyone who read the previous books

How the Book Changed Me

No changes – perhaps a further enforcement of the view that societies are very complicated things and the thought that disparate groups would unite in the face of a common threat is actually an attribute of very advanced societies.

Summary + Notes

For me it proved a first-class travel agency, sending me at His Majesty’s expense to countries that I could never otherwise have hoped to visit.

Juliet was a trim and self-possessed young woman with soft brown hair, faultless curves and inviting dark blue eyes. Most of her advice on the Far East proved inaccurate; she did, however, give me a few tips of more lasting value, and she was a sparkling, even bewitching companion and partner in pleasure.

A heavy rucksack, I told the training staff, was a white man’s burden that I was not prepared to tote; a small haversack such as had served me well in Albania and Poland was the most I would allow to aggravate my prickly heat; anything bulkier must be carried by mule, pony, bullock-cart or local labour—or abandoned. I never had cause to change this view.

I could only recall the bitter words of Colin Ellis’s epigram: ‘Science finds out ingenious ways to kill Strong men, and keep alive the weak and ill, That these asickly progeny may breed: Too poor to tax, too numerous to feed.’

In the excitement and fatigue of the last few days I had forgotten that this was indeed my thirtieth birthday, 19th August 1945.

The soil is poor and so, therefore, are the people, who supplement their income by breeding water buffalo, oxen and pigs for export to other parts of the country. But poverty has not brought discontent; most of the land is owned by the peasants who till it, and those twin vultures, the absentee landlord and the money-lender, cannot prey here as in India and in Lower Siam.

The Chinese, on the other hand, though not loved were tolerated; they owned all the hotels and eating houses and, together with the Indians, all the shops.

I received also a great deal of information that turned out to be false. The problem of sifting true from inaccurate reports was one that I was never able to solve the whole time I was on the frontier; I was at the mercy of my agents, who turned out as often as not to be double agents.

Another of his duties was to supervise the disarming of some eleven thousand Japanese and the shooting of their horses, which were in terrible condition, having been shamefully neglected by their masters. He was astonished, therefore, to see the Japanese soldiers in tears as they shot their horses, and then to watch them remove their caps and bow for two minutes before filling in the graves, which they covered with flowers.

Although the capital of the Laotian province of Cammon, Thakhek had a very large Annamese population, which in fact outnumbered the Laos; in the countryside, on the other hand, there were comparatively few Annamites, for they tended to congregate where there was some form of industry to give them employment. There was no love lost between the two races. The majority of Laos stood by the French, whereas the Annamites detested them and, having collaborated actively with the Japanese, were now organizing themselves into a Communist movement, with the declared intention of expelling the French from the whole of Indo-China; this movement was the Viet-minh. Now the Annamites, having obtained large supplies of arms from the Japanese, would, after the departure of the latter, control Thakhek. Tavernier’s troops were too weak and poorly armed to drive them out; indeed, they would be lucky to hold their own.

When the Japanese occupied French Indo-China in 1940 they did so with the acquiescence of the Vichy authorities who at that time ruled the colony; the French Colonial Army had orders not to resist. Until March 1945 the Japanese were content to use the country as a base, leaving the administration in the hands of the French, whose soldiers retained their arms.

The headman, who spoke pidgin French, procured us the men we needed; but it took time to assemble them, for hurry is a word unknown in the Laotian vocabulary.

During our talk the Annamese insisted on producing for our close inspection the very messy bodies of their dead—as Smiley commented, they must have been unattractive enough when alive.

A few days of rest, decent food and, above all, freedom from fear, worked amazing changes in their appearance, especially among the women. After observing the effects of a little make-up and a lot of ingenuity on one or two of the girls, I began to regret that present circumstances did not allow me to cash in on my position as their liberator and protector.

Although since the last century, when they had annexed Cambodia, the French had been the immediate object of Siamese fear and suspicion, always there had been the remoter but much more formidable menace of China.

The American attitude was summarized by the late Mr. Chester Wilmot, who wrote, ‘Roosevelt was determined that Indo-China should not go back to France.’ Mr. Graham Greene, who visited the country early in 1954, wrote of American intervention: In 1945, after the fall of Japan, they had done their best to eliminate French influence in Tongkin. M. Sainteny, the first post-war Commissioner in Hanoi, has told the sad, ignoble story in his recent book, Histoire d’une Paix Manqée—aeroplanes forbidden to take off with their French passengers from China, couriers who never arrived, help withheld at moments of crisis.

We were shortly to witness even worse. Like ourselves the French had been accustomed to thinking of the Americans not only as allies but as friends; it never occurred to any of us simple officers that the most powerful country in the free world would deliberately embark upon a policy of weakening her allies to the sole advantage of her most dangerous enemy. We have learnt a lot since, but in those days it all seemed very strange.

At the end of the month the Chinese arrived in strength. Almost their first action was to invite all the French officers to a dinner-party. At the Chinese headquarters in the Residency, where the tricolour was flying in their honour, Fabre and his companions were courteously shown into a room and immediately surrounded by Chinese soldiers with levelled tommy-guns. They were relieved of their arms, equipment, money and watches and ordered to quit the town instantly, on pain of arrest. After some argument Fabre himself was allowed to stay, together with his wireless set and operator; but he had to send the rest of his force ten miles away, for he had been ordered to avoid incidents with the Chinese.

Banks assured them that he was determined to put an end to what he called French aggression; also that Chinese troops would shortly arrive to disarm the French and take over the administration of the country pending the establishment of a ‘national and democratic government’ in Indo-China, free from the rule of France.

I reflected that if it were true, as we had heard, that the Viet-minh had Japanese deserters in their ranks, it was lucky for us that none of them was behind those guns.

Cox was a clever and experienced officer who had served with Force 136 in Burma; his gift for extracting the maximum amount of quiet fun out of life made him a delightful companion. Maynard was a young man of twenty-two whose ingenuity and enthusiasm more than compensated for any lack of maturity. Powling, a tall, quiet, very young soldier, most efficient at his job, unfortunately died the following January from virulent smallpox.

The girls were not prostitutes; they would take no money from us, but gave themselves over with uninhibited abandon to the pleasures of the night. Their attitude was not untypical, in my experience, of the Siamese outlook on sex which seemed to be compounded of equal parts of sensuality and humour.

Nothing so concentrates a man’s mind, observed Dr. Johnson, as the knowledge that he is going to be hanged.

My intention had been to apply at once for the demobilization to which I was now entitled. But while waiting in Bangkok I was offered and immediately accepted the command of a mission to the islands of Bali and Lombok in the Netherlands East Indies. There the Japanese garrisons had not yet surrendered, and the situation in both islands was obscure; SEAC therefore decided to send in a small advance party of British troops before committing the Dutch forces of occupation.

Tolerance and mercy are qualities seldom found in twentieth century revolutionaries.

whenever I have to give orders to clear out a nest of snipers that’s been harassing my men I seem to feel the hot, angry breath of Socialism on the back of my neck. So

I had never met Japanese in battle, the most I had had to do was keep out of their way. Now in my unearned hour of triumph I felt ashamed to watch this veteran sailor, who had spent his life in a service with a great fighting tradition, weeping openly over his humiliation at the hands of a jumped-up young lieutenant-colonel who had never even fought against

Lying between eight and nine degrees south of the Equator Bali naturally enjoys a warm climate and an even temperature throughout the year; there is in fact less than ten degrees variation between the warmest and coolest months. Sea winds preserve the island from the burning heat of other equatorial lands, but from November until April the north-west monsoons bring heavy rainfall and the discomforts of a high humidity; the pleasantest months are from June to September, when a cool, dry wind blows from Australia.

In their fear and hatred of the sea the Balinese are exceptional among island peoples. At Sanoer I saw men wading in the lagoon a few yards off shore with casting nets, or putting to sea in canoes with triangular sails and curiously carved and painted prows, to hunt the sea turtles that are a favourite delicacy at banquets; but most Balinese avoid even the coast and the beaches. In the words of Covarrubias ‘they are one of the rare island peoples in the world who turn their eyes not outward to the waters, but upward to the mountain tops.’

Every adult male Balinese, he says, was obliged to contribute a tax to his rajah in the form of work; if a man died without leaving a son old enough to take over this work, his widow and female children became the rajah’s property. Old women were employed in the palace, the middle-aged put to heavy manual labour; but the young girls—often before the age of puberty—were forced to become prostitutes and pay as much as nine-tenths of their earnings to the rajah. In Badung, the old principality of Den Pasar, Dr. Jacobs met several of these prostitutes under the age of puberty. Each rajah owned between two and three hundred of these unfortunate girls—a considerable source of income.

It is true that Hindu gods and practices are constantly in evidence, but their aspect and significance differ in Bali to such an extent from orthodox Hinduism that we find the primitive beliefs of a people who never lost contact with the soil rising supreme over the religious philosophy and practices of their masters. . . . Religion is to the Balinese both race and nationality.

Certain acts or conditions of individual members can make the whole community sebel, or unclean, and therefore vulnerable to evil forces. Such acts extend beyond the unpardonable crimes of suicide, bestiality, incest and the desecration of a temple, to quite innocent or unavoidable breaches of taboo; a menstruating woman, for instance, is sebel and must be secluded, and parents who have twins will render their village sebel. To such a people, in the words of Mr. Raymond Mortimer, ‘sin is not a disregard for conscience but a breaking, no matter how unintentional, of a taboo; and the resulting pollution can be removed only by ritual cleansings and sacrifice.’

There are four main castes, of which more than ninety per cent of Balinese belong to the lowest, the Sudras. The three noble castes are the Brahmanas, the priests; the Satrias, the princes, and the Wesias, the warrior caste. All three claim divine origin—from Brahma, the Creator—which is probably why the common people hold them in such respect. The Brahmanas are theoretically the highest, although the Satrias are inclined to contest their superiority; their influence is religious rather than political, but they serve as judges in the courts; their own laws forbid them to engage in commerce. Brahmana men carry the title Ida Bagus, and the women are styled Ida Ayu, both meaning ‘Eminent and Beautiful’. The two principal titles of the Satrias are Anak Agung, ‘Child of the Great’, and Tjokorde, Prince. Most of the nobility, however, belong to the Wesias and carry the title, Gusti; they have considerable political influence.12

There do not seem to be any ‘untouchables’, as in India, but certain professions are ‘unclean’ and will pollute a village if practised within its boundaries; among them are, strangely enough, pottery, indigo-dying and the manufacture of arak—a powerful, fiery spirit distilled from the juice of the sugar palm.

Only the laws of marriage are inflexible between the castes. A man may marry a woman of an equal or lower caste, but never may a woman marry a man of lower caste; even sexual intercourse between the two is forbidden, and in former times was punishable by the death of the guilty pair.

The most terrible of all punishments for a Balinese is expulsion from the village, when the offender is publicly declared ‘dead’ to the community; when the Dutch abolished the death penalty this became the capital punishment. ‘A man expelled from his village cannot be admitted into another community, so he becomes a total outcast—a punishment greater than physical death to the Balinese mind. It often happens that a man who has been publicly shamed kills himself.’

‘Childlike’ is the label attached in this hideous age to a people unresponsive to the language of the demagogue, the high-pressure salesman and the advertising hound; it is a label that bears no resemblance to the character of the Balinese, although they prefer their traditional way of life to that of the modern world, which, they would certainly agree with Pierre Louÿs, ‘succombe sous un envahissement de laideur.’ They have neither the ignorance nor the innocence of childhood, although they give an impression of its simplicity. They are, as I have said, the most skilful agriculturists in Asia, they are painters, craftsmen, poets, musicians and dancers; and their art has aroused the envy of a civilization to whose arrogance, ugliness and brutality they are largely indifferent.

The enthusiasm of the Balinese for this sport is as intense as that of the British for football or the Spanish for bulls; in ancient times, indeed, men would sometimes gamble away their whole fortunes in cockfights, even staking their wives and children. It was for this reason that the Dutch government intervened.

Moreover, unlike the Common Law of England, Balinese law does not hold a husband responsible for his wife’s debts.

Leaving the Buffs by the car Shaw and I approached the Pemudas; we put on the most nonchalant air we could muster, but for my part I know that my stomach felt full of butterflies and, as the Spaniards so prettily express it, my testicles were in my throat.

‘No, and I don’t suppose they care either. It must be all the same to these highlanders whether the Dutch, the Nips, the British or their own people are in power. Nobody seems to have bothered about them; they look as if they live pretty near the starvation level, and I’m sure they wouldn’t recognize a social conscience if they saw one.’

by the early symptoms of the tuberculosis which eighteen months later almost ended my life. Apart from the usual persistent cough, to which I paid no attention, I became noticeably neurotic, short tempered and snappy, with spells of overpowering lassitude that seemed to deprive me of all my energy and will. At the time I put everything down to war-weariness and alcohol.

Why they made no attempt to kill us all is something I can only attribute to Hubrecht’s personal popularity with the Balinese, and to the well-known Oriental affection for lunatics and children.

It occurred to me now that I was just two months short of my thirty-first birthday and for ten years I had been almost continuously at war; I wondered how I should make out in peace.

-

Atomic weapons thought experiment

A thought experiment

Suppose that on the eve of Germany invading Poland Hitler has a debilitating stroke or a heart attack and power is seized by a loose collection of his underlings. They do not attack Poland (high risk, Hitler was the gambler among them) and consequently they do not go to war with France and the UK.

Germany and the USSR continue rearming, so does France, the UK and to a lesser degree, the US.

Japan continues it’s war in China but does not initiate conflict with any of the US and European powers (low upside, high downside risk if there is no war with Germany)

German keeps control of it’s various territories, Austria, Sudeteland(sp), Checkoslavakia, etc .

The world slips into a cold war type arrangement, similar to the US and Soviet Union in 1955, but more dispersed

Proxy wars abound, in a much more complicated way, but no great power conflicts.

The question – does anyone on any side develop nuclear weapons in this scenario? The Manhattan project was insanely expensive and was competing only with other military projects, and had an immediate use. If there was no immediate use, no sense of national urgency and was competing with both civilian and military uses for the funding – would anyone on any side have bothered to develop atomic weapons at that cost, both financial and talent?

This came up on the Lunar Society podcast with Richard Rhodes – he thought that the technology had too much promise to go undeveloped, which I thought too, but after more thinking about it I am no longer sure. It was an obvious choice in a military/war environment, less obvious in a high tension peace environment. The Star Wars program of the 1980s (a very imperfect comparison) would suggest that atomic weapons would not be developed.

Update – I ran this by a group of very smart people, all of whom disagreed with me. I am still somewhat convinced of my position though.

-

No Colours or Crest: The Secret Struggle for Europe by Peter Kemp

From my Notion template

The Book in 3 Sentences

- The second of the Peter Kemp war books – it details the bulk of the Second World War for him. By odd twists of fate, he volunteers for the most dangerous jobs imaginable, but is first (mostly) constrained by weather – then by terrain , then by people. Functionally his job changes from commando, to would be guerilla leader to outside sales, where the penalty for failure to meet quota is perhaps death. The sales job was trying to organize Albanian guerilla groups into an effective fighting force, which did not happen.

Impressions

This seemed a lot like a diary that he filled supplemented with the benefit of hindsight, after action reports and historical perspective, which is not a bad thing, but the prioritization is odd – the march up the hill for the ambush that gets rained out gets the same number of pages and emphasis as getting chased by German patrols.

How I Discovered It

I read his first book – “Mind Were of Trouble”

Who Should Read It?

World War Two history buffs, people interested in the Balkans

How the Book Changed Me

How my life / behaviour / thoughts / ideas have changed as a result of reading the book.

- A reaffirmation on the importance of geography, weather and culture in history

- A reaffirmation that there are winners and losers in all things

- A reminder that the modern way of life, Britain in this time period would qualify, existed with other ways of life until quite recently in much more of the world than I would have thought. The existence of blood feuds being binding restraints on nationwide political movements was quite interesting. The primary political unit is not always the nation, or even the party, but also the family and extended family in a lot of the world.

- I am now wondering how much of history was written by the victors in Eastern Europe – the standard narrative does not seem to be quite complete.

Quotes

A strong Tory myself, I had served in the Carlist militia and the Spanish Foreign Legion, where my friends—Traditionalists, Conservatives and Liberal Monarchists—had no more sympathy than I for totalitarian regimes. But General Franco’s friendship with Hitler and Mussolini and his establishment of the Falange as the only political party in Spain had erased from most British minds all memory of the Communist threat he had defeated; even the Soviet-German Pact had not wholly revived it.

Poor Greta. She was a wonderful cook. But her naïve optimism did not save her from nearly six years in an internment camp.

I was all too conscious of my failure to set a proper example of indifference and courage. When the All Clear sounded I reflected sorrowfully that the last three years had left their mark upon my nerves.

He nursed a particular resentment against Hitler for what he regarded as an intolerable interruption of his private life. ‘Up to the age of thirty-five,’ he explained to me, ‘a man can work and drink and copulate; but at thirty-five he has to make up his mind which of the three he is going to give up. I had just passed my thirty-fifth birthday and made all my arrangements to give up work when that bloody Hun started the war.’

Easily the most junior of our party, I was delighted to find myself promoted overnight to the rank of Captain, which seemed to be the lowest rank on our Establishment.

This new organization, known as S.O.E., became responsible for all subversive activities in enemy-occupied territory. It received its directives through the Minister of Economic Warfare, and was staffed, surprisingly, by senior executives from several large banking and business houses, with a small but useful leavening of Regular Army officers, a few of whom had received Staff College training.

‘Save and deliver us, we humbly beseech Thee, from the hands of our enemies; abate their pride, assuage their malice, and confound their devices.’

took advantage of my leave to get married. Looking back from time’s distance I wonder how I could have been so foolish, complacent, and blind to my own character as to ask any girl, at my age and at such a time, to marry me; it is scarcely less remarkable, I suppose, that any girl who knew me well—and this one did—should have considered me a suitable husband. Our marriage lasted almost, but not quite, to the end of the European war.

In London, when we arrived after completing the course, my greeting from the staff officers of the Spanish section was not such as a hero might expect. Coldly the R.N.V.R. lieutenant said to me, ‘Perhaps you would care to read the concluding words of Major Edwards’s report on you?’ They ran simply: ‘Not once, nor twice, but three times have I seen this officer punctual.’

By religion a deeply sincere Roman Catholic, by tradition an English country gentleman, he combined the idealism of a Crusader with the severity of a professional soldier.

Thus, although we were also known as No. 62 Commando and were issued with green berets, March-Phillipps encouraged us to wear civilian clothes when off duty; this was in keeping with his conception of us as successors to the Elizabethan tradition of the gentleman-adventurer.

Reynolds was an Irishman, well known before the war as a sportsman, bon viveur, and playboy. On the outbreak of the Russo-Finnish war in 1939 he went to Finland as a volunteer in Major Kermit Roosevelt’s International Brigade; having exchanged the comfort and cuisine of Buck’s for the icy forests of Lapland and Karelia, he endured bitter hardship with that ill-fated band of idealists before making his way to Sweden after the collapse of Finnish resistance. There

leave, I was ordered by Brigadier Gubbins to take a party of our officers on the parachute course at Ring way. I had been sleeping badly, with terrible nightmares of those screaming sentries, and I was glad of an opportunity to take my mind off the recent raid.

For a few months the supporters of Tito and Mihailović had worked together, although with mutual suspicion, for they were fundamentally opposed in outlook and objectives. By the end of 1941 their hostility to each other had flared into open warfare, so that their efforts were wasted in internecine strife.

Although Mihailović still enjoyed the official support of the British Government, Tito was not without friends in S.O.E.: one staff officer, in fact, so far allowed his enthusiasm to exceed his discretion that he was subsequently tried and convicted under the Official Secrets Act for passing confidential information to the Soviet Embassy in London.

in 1936, he had been the secretary and inspiration of the Cambridge University Communists. I had innocently supposed that Communists were strictly excluded from S.O.E., for I myself had been required to sign a declaration that I belonged to no Communist or Fascist party before I was enrolled in the organization. However, among my acquaintances at Cambridge there were a number of young men who had joined the Party in a spirit of idealism, only to leave it after the Soviet-German pact of 1939; I assumed that Klugmann was one of them. But I was wrong: like his contemporary, Guy Burgess, he was one of the hard core and today he is a member of the Politburo of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

At this time the social structure in the north was tribal, resembling that of the Scottish highlands before the Forty-five; in the south a rich landowning aristocracy exploited a landless peasantry which since the beginning of Turkish rule had been allowed neither the security of wealth nor the dignity of freedom.

There are three religions in the country, generally confined within geographical limits: in the south the majority of the peasantry is Greek Orthodox, though the land-owning Beys are Moslem; the centre and plains are predominantly Moslem, while the north is divided between the Catholic mountaineers of Mirdita and Djukagjin, and the Moslems of Kossovo and the wild north-eastern frontier. But religious differences seemed to be of little importance in comparison with the rivalry of Gheg and Tosk and the age-long hatred of both for their Slav and Greek neighbours. At

the end of the Balkan Wars the Ambassadors’ Conference of 1913 recognized Albania as an independent State, delineating for it frontiers which were acceptable neither to the Albanians nor to their neighbours.

Two years later he was back in the mountains of Mati, where he carried on a guerrilla war against the Italians and their German successors until the end of 1944, when he was overrun and driven into exile by the Communists who now dominate his country. In

‘In practice, exclusive control of the movement was retained in the hands of a small committee, all of whom were Communists. This committee, besides directing policy, appointed the guerrilla commanders, the political commissars, and the regional organizers. The former were most often, and the two latter invariably, Communists; while, in accordance with the best conspiratorial traditions, all three were kept under observation by Party members who held no official position at all. By these methods, seconded by the salutary liquidation of those who disobeyed or disagreed, the Partisan movement presently achieved a degree of discipline and cohesion of which few observers believed Albanians to be capable.

gradually became apparent that the arms and money which S.O.E. was dropping so lavishly into Albania were being conserved by L.N.C. and Balli Kombëtar alike for use against each other.

These instructions, which seemed clear and logical to us in Cairo, were to prove quite unrealistic in the field.

he had volunteered for Albania, he informed us, in order to keep himself in practice for his next Himalayan attempt.

Reading this last sentence I was reminded that the Encyclopedia Britannica listed the word ‘intelligence’ under three headings: 1. Human; 2. Animal; 3. Military.

Unlike most of the Partisan leaders he already had some practical experience of serious warfare, for he had commanded a company of the International Brigades in Spain; unlike most of them, also, he spoke good English. A sour, taciturn man of ruthless ambition, outstanding courage, and sickening ferocity—he had personally cut the throats of seventy Italian prisoners after a recent engagement—he tried hard to conceal his dislike and distrust of the British, because he admired the soldierly qualities of McLean and Smiley and valued the help they gave him.

the whole L.N.C. movement—was in the hands of the Chief Political Commissar, Professor Enver Hoxha, an ex-schoolmaster from the Lycée at Korçë. He was a tall, flabby creature in his early thirties, with a sulky, podgy face and a soft woman’s voice. Like Mehmet Shehu he was a fanatical Communist, cruel, humourless, and deeply suspicious of the British. He spoke excellent French but no English. Although physically a coward he had absurd military pretentions, which led him two years later, when his forces had made him master of Albania, to arrogate to himself the rank of ‘Colonel-General’. It

No wonder the villagers are fed up! They must either take to the hills and lose their property, or stay and be massacred. Sometimes, to escape reprisals, they do warn the enemy of L.N.C. ambushes, and it’s hard to blame them.

If I had been entranced before I came to Albania by the romance and glamour of guerrilla warfare, this was a sobering reminder of its squalor and injustice.

Enver Hoxha and Mehmet Shehu were not building up their military formations in order to fight Germans or Italians, but in order to gain control of Albania for themselves by force; they were not going to risk serious losses in operations which to them were only of secondary importance.

Now a Bektashi monastery stood on the slopes. The Bektashi sect, which was influential in Albania, seems to have originated during Turkish times among the Janissaries and contains elements of different religions absorbed into the Islamic faith. In particular, its adherents are not forbidden the use of strong drink.

In accordance with custom our arms were taken from us when we entered the house. This gesture signified that as long as we were under his roof our host was responsible with his life for our safety; if anyone were to kill us our host must start Hakmarjë—a blood feud—with him and would be dishonoured in the eyes of all his neighbours until he avenged our death with that of the murderer. The

It was not unusual for as many as twenty members of one family to be killed in the same vendetta in the course of two or three generations.1 More than once an Albanian has said to me: ‘I cannot go with you to that house; I have enemies.’

few months after his appointment to command the Italian Partisans in Albania he absconded to the mountains, accompanied by his Staff, with a considerable sum of money given him by the Allies to feed and equip his men.

As soon as he heard the news of the surrender, on 9th September, Seymour hurried to Arbonë, where he sent a message to General Dalmazzo in Tiranë requesting his co-operation and asking for a meeting; unfortunately the message was not delivered until the next day, when the Germans were already in occupation of the capital. However, Dalmazzo sent a staff car to Arbonë, which took Seymour, wearing an Italian army greatcoat over his uniform, through the German control posts to Army Headquarters, where he had a long discussion with Dalmazzo’s Chief of Intelligence. At the same time, in an adjoining room, Dalmazzo himself was in conference with senior German officers, arranging his own evacuation under German protection to Belgrade; not until Dalmazzo had left Albania did Seymour learn the truth.

Moreover, to many patriotic Albanians it was by no means clear that an Allied victory was in the best interests of their country; they feared—perhaps I should say fore-saw—that it would result not only in the loss of Kossovo but also in their own subjection to Communist rule.

The Germans played cleverly upon these feelings. Firstly they made very few demands on the civilian population, to whom they behaved with courtesy and consideration, and secondly they made much political capital out of the Kossovo question. It is a measure of their success that when they set up a puppet government in Tirana they were able to induce Albanians of high principles and distinction to serve in it. As time went on it became more and more obvious that we could offer the Albanians little inducement to take up arms compared with the advantages they could enjoy by remaining passive.

we British Liaison Officers were slow to understand their point of view; as a nation we have always tended to assume that those who do not whole-heartedly support us in our wars have some sinister motive for not wishing to see the world a better place. This attitude made us particularly unsympathetic towards the Balli Kombëtar, although the latter was a thoroughly patriotic organization. The Balli refrained from collaboration with the Germans against us; indeed, they gave us much covert help; but they did sit on the fence, hoping to establish themselves so firmly in the administration of the country that the victorious Allies would naturally call upon them to form a government. Indeed, they were naïvely convinced that the British and Americans would be glad to entrust the government to them, in preference to the Communist alternative of the L.N.C. The leaders of the L.N.C. had good reasons for continuing the struggle; but their interests, of course, were not Albania’s.

He did nothing to raise my spirits by pointing out how conspicuous I should appear in the town, for not only did I look like a foreigner but I even walked like one; to the vast entertainment of Seymour, Myslim, and Stiljan he insisted on giving me lessons in the ‘Albanian Walk’. He was not impressed with my progress.

I had come to Tiranë unarmed, believing that a gun was more likely to get me into trouble than out of it.

Cairo agreed to drop the money, but in small amounts, and to disperse it among the various British missions in the country, hoping thus to control its expenditure. The result was the same: most of the money was diverted to finance the Albanian Communist Party, who took exclusive credit for such relief work as was done.

but I was unable to shake off the feeling that they intended to keep one foot in the German camp in order to conserve their strength for the real struggle for power with the Partisans.

From his first days in Albania he suffered continuously from dysentry, but his spirit and determination drove him to endurance far beyond his strength.

At first sight Fiqri Dine reminded me of an evil, black, overgrown toad; his manner was reserved and barely friendly, his speech patronizing.

In Dibra, we subsequently heard, the Germans had received a similar ovation; disgusted with the behaviour of the Partisans and grateful to the power that had united them with their kin in Albania, the Dibrans had turned their backs on the Allied cause.

But it derived also from the perpetual insecurity of life in the mountains, especially on the frontiers; there were very few families whose houses had not been burnt at least once this century by Turks, Serbs, Greeks, Austrians, Germans, Italians, or fellow Albanians.

must have shocked the Germans’ own allies, for even in their blood-feuds the Albanians would respect the lives of women and children.

he looked very frail, sitting in a corner swathed in bandages, but his wounds were healing well under the usual local treatment, which was to plug the bullet-holes with goat’s cheese.

My principal task was to explore the chances of forming a resistance movement among Albanians in Kossovo. When I sounded him on the subject Hasan Beg warned me, as I had feared he would, that the majority of Kossovars preferred a German occupation to a Serb; the Axis Powers had at least united them with their fellow Albanians, whereas an Allied victory would, they feared, return them to Jugoslav rule. Therefore, although most believed that the Germans would eventually be beaten, few would risk their lives to help in the process without some combined declaration by the Allied governments, guaranteeing the Kossovars the right to decide their own future by plebiscite.

when I was awakened by the sound of three rifle shots in quick succession; grabbing their weapons Zenel and the others ran outside, to return in a few minutes with the comforting assurance that it was only a tribesman settling accounts with his blood-enemy.

‘Old man, it looks as though you’ve walked out of one spot of bother straight into another. There’s a blow-up expected here any day between the Partisans and the local chiefs.’

I did not mention the matter in front of Salimani because he had a feud with the Kryezius, dating from the 1920s when the eldest Kryeziu, Cena Beg, had invaded Krasniqi with a force of gendarmerie to hunt down his outlawed rival, Bairam Curi. I heard more of this tale later.

I ordered them to return to Deg at once, adding that the Kosmet could do what they liked about it. What they did, I soon discovered, was to send word to the Germans that I was in Gjakovë.

Soon we were prowling through the twisting, cobbled streets of the town like small boys playing Red Indians.

In the calm yet menacing grandeur of that mighty massif looming through the twilight I saw embodied all the splendour and savagery of the Balkans; all the harsh nobility and fierce endurance of the land shone in the opalescent beauty of those ice-bound, snow-wrapped cliffs.

was painfully reminded of the local name for these mountains—Prokletijë, or Accursed.

‘We have nothing against you English,’ he added. ‘Only we don’t want the Communists here; and so we collaborate with

those whom they considered to be our friends. In the eyes of the new rulers of Albania collaboration with the British was a far greater crime than collaboration with the Germans.

Of the Partisan leaders with whom I worked some have survived to enjoy power and privilege: others have been devoured by the monster they helped. to rear.

Albania, now the most abject of the Russian Satellites, was a totally unnecessary sacrifice to Soviet imperialism. It was British initiative, British arms and money that nurtured Albanian resistance in 1943; just as it was British policy in 1944 that surrendered to a hostile power our influence, our honour, and our friends.

but it was not the disappointment or the boredom that irritated us—not even the needling of the Partisans—so much as the knowledge that we were sitting idle in a backwater while great things were happening in the war outside. I thank heaven that I was never so unfortunate as to become a prisoner of war.

These supplies came from the Americans, but the Political Commissar used all his ingenuity to persuade his men and the peasants that they came from Russia. He went to the trouble of explaining that the initials, U.S. which were clearly stamped on the packages stood for ‘Unione Sovietica’; had not the planes been Italian? Then of course the labelling would be in Italian.

‘At least refrain from treachery to your officers in the field. Such conduct is unworthy of prostitutes let alone S.O.E. Staff Officers.’ He very rightly rejected my amendment, which would have read: ‘Such conduct is unworthy of prostitutes or even S.O.E. Staff Officers.’

Quayle had just come out of Albania from the Valona area, where his life had been an uninterrupted nightmare in which the Germans had played only the smallest part.

I suppose that eight months in the Balkans can be lethal to anyone’s sense of proportion.

He proposed to send me to Hungary to work with a non-Communist resistance group near Gyöngyös, north-east of Budapest. I should have to drop in the Tatra mountains in Slovakia, where the Slovak army was in revolt against the Germans, and cross the frontier to Hungary. It sounded an interesting assignment in a part of Europe that I had always wanted to visit.

In the years since the disruption of that curious manage a trois, the Anglo-American honeymoon with Russia, the various instances of Soviet treachery have faded from our memory, dulled either by the passage of time or by the frequency of repetition. The story of the Warsaw rising, however, provides a particularly odious example. In July the Red Army summer offensive across Poland was halted on the Vistula by the German Army Group Centre under Field-Marshal Model; on 1st August Russian forces under Marshal Rokossovsky—himself a Pole—were only five miles east of the capital. At this critical moment the Polish Home Army rose in revolt, joined by the entire civilian population of Warsaw.2 It may be that the rising was premature and that supply difficulties and heavy German reinforcements held up the Russians; perhaps the Poles were unduly sanguine if they forgot for the moment that it was the stab in the back from the Red Army in 1939 that brought about the final collapse of their resistance to the Germans, or if they expected Stalin to forget the great Polish victory on the Vistula in 1920 which drove the Red Army from their country. Nothing, however, can excuse the Russian failure to lift a finger in support of Bór-Komorowski; most infamous of all, the allied aircraft flying from Britain and Italy to drop supplies to the beleaguered Poles were refused permission to use the Russian airfields near the city. Knowing that the Armja Krajowa was opposed to Communism in Poland, Stalin was delighted to watch its destruction at the hands of the Germans; in the words of Dr. Isaac Deutscher, usually a sympathetic biographer, ‘he was moved by that unscrupulous rancour and insensible spite of which he had given so much proof during the great purges.’3 After a few weeks of lonely and heroic resistance, during which the Germans systematically reduced Warsaw to rubble, the remnant of the Polish garrison surrendered.

We were also handed, in an atmosphere of grim and silent sympathy, a small supply of ‘L tablets’, each containing enough cyanide to kill a man in half an hour if swallowed, in a few seconds if chewed; the idea was that we might find ourselves in circumstances where suicide would be preferable to capture. Fortunately or unfortunately we somehow mixed them up with our aspirin tablets and so decided to destroy our store of both.

We lived in a trullo, one of the beehive-shaped dwellings that are typical of the Apulian hill country. These quaint and cosy buildings, warm in winter and cool in summer, are said to date from pre-medieval times when taxation was levied on every house with a roof; their ingenious construction requires no mortar, the bricks supporting one another from foundations to ceiling, so that the roof could be quickly removed on the approach of the tax collector and as quickly replaced after his departure. From the terrace of our trullo on the hillside we looked eastward over silver-green olive groves to the lead-coloured waters of the Adriatic.

At first I thought my parachute must have been late in opening; but it turned out that the pilot, either through an error of judgment or in the excitement of finding himself so close to his native land, had dropped us all from a little over two hundred feet. If any of our parachutes had failed to open immediately there would have been a fatal accident.

It is well known, although it can bear repetition, that Poland alone among the countries occupied by Germany produced no Quisling.

As far as I know we were the first and only British officers to be dropped into the country.

Most savage of all were the German auxiliary troops belonging to the army of the renegade Russian General Vlasov. Vlasov was a Cossack who was captured at the beginning of the German offensive against Russia in 1941 when, according to some figures, eight hundred thousand Russian soldiers were taken prisoner. From these Vlasov recruited an army of Cossack, Ukrainian, Turkoman, Mongol, and other Asiatic troops, which the Germans employed chiefly on garrison and security duties in occupied countries. Knowing that they would receive no quarter if taken, these men fought to the last; such was their barbarity towards the civilian population that they were feared and detested throughout occupied Europe. In this part of Poland there were Ukrainian and Turkoman divisions on the river Pilica and Cossack patrols everywhere. The A.K. shot any of Vlasov’s men whom they captured, as they also shot all S.S. men; prisoners from the Wehrmacht were usually deprived of their arms and uniforms and then released.

We commented on the lack of interest that all of them, old and young, showed in the personalities of the exiled Polish Government in London—an indifference which we found everywhere in Poland. Mikolajczyk alone seemed to have a considerable following. It has often been remarked that governments in exile tend to lose touch with the people they claim to represent; they tend also to lose their respect.

with astonished admiration I saw that a detachment of our escort had emplaced itself behind a low bank and was firing on the tanks and the advancing infantry: some twenty-five Poles with rifles and one light machine-gun were taking on four tanks and at least a hundred well-armed Germans.

If there is any more disagreeable experience in warfare than that of running away under fire I hope I never meet it. There is none of the hot excitement of attack, but much more of the danger;

At that time, of course, the whole problem seemed academic and unreal; none of us could foretell the hideous future, none of us remembered Stalin’s pledge to Hitler in 1939 that Poland should never rise again; least of all could we suppose that those apostles of freedom, Britain and the United States, would underwrite by treaty such an odious conspiracy.

During the three days of our stay we became infested with the most prolific and ferocious crop of lice that I at least have ever encountered. For the Spanish, Albanian, and Montenegrin louse I had learnt to acquire a certain tolerance, even affection; but these creatures bit with an increasing and fanatical fury that excluded all hope of sleep and comfort.

As the evening progressed, the pace of the party quickened to a macabre and frenzied gaiety whose implications could no longer be concealed. However much these people hated the Germans—and there was not a man or woman in the room who had not lost at least one close relative fighting against them—they literally dreaded the Russians. Tonight they were saying good-bye to the world they had always known. The German occupation had brought unbelievable hardship and tragedy to their country and their class: Russian rule, they foresaw, meant extinction for both.

the Red Army’s method of living off the country during an advance was as devastating as their ‘scorched earth’ policy in retreat.

Such was the routine of our prison life. The N.K.V.D. had taken over the building from the Gestapo only two days earlier—with all fittings.

-

Quote of the Day Jeffrey Lewis edition

From here

So I threw out some past to make room for more future

and

I see a better person waiting his turn to be me

-

My definition of Woke – the short version – take 1

Since this seems to be all the rage – I hereby offer my definition of “woke”

I define “woke” as a belief that society is by default divided into two groups – the oppressors and the oppressed. All social interactions are a zero sum conflict between those two groups. All of history is merely a record of this conflict and nothing else. By default neither group can see this model of reality. However, it is possible for people to see the world accurately for one reason or another. (the process of this realization varies and is not essential to the worldview). This worldview is largely an extreme version of a class based view of the world, however instead of dividing the world up into “workers” and “capitalists”‘ there are many, many more subgroups who make up the oppressed class, and many more subgroups that make up the oppressor class.

By virtue of having this knowledge one can see the hidden threads throughout history and choose to exercise virtue, which is by advocacy for particular groups in the oppressed class. This is largely expressed as secular evangelism for those groups, and active efforts to reduce the social status of the oppressor class groups.

The pose is that of evangelism, i.e. convincing people to see the world their way, but the tactics are all destructive, in terms of social media and social status. The focus is entirely on raising and lowering the social status of different groups.

This worldview is notable for being younger, more tied to social media, fashionable consensus, signaling and being disproportionately female. I suppose a common sense of alienation from society is a necessary part of the definition as well.

-

Quote of the Day

A dog with two masters starves to death.