-

Never Enough: The Neuroscience and Experience of Addiction by Judith Grisel

From my Notion template

The Book in 3 Sentences

- This book is an extremely readable book from both the personal and scientific side of addiction. The author, once a street addict, and currently a neuropsychologist, explains how drugs affect the brain and body quite well and fills in the gaps that other books miss. The root point is that the body is biologically tuned for homeostatis/normalcy and this, via a weird series of biological processes will lead to addiction – there is never enough drug to keep one high forever.

Impressions

This book is by far the best book on the mechanics of addiction, why it happens, how it happens, and why it is so hard to make it “unhappen”

How I Discovered It

A Tyler Cowen blog post

Who Should Read It?

Everyone really – it clarifies all thinking on both drugs and a lot of behavior.

How the Book Changed Me How my life / behaviour / thoughts / ideas have changed as a result of reading the book.

- I now think much more of counterreactions

- I now see things as more of a Process A vs Process B axis (in terms of physical matters)

My Top 4 Quotes

- Data such as these suggest that some of us are especially likely to find alcohol reinforcing because we can use it to medicate an innate opioid deficiency. Perhaps the “hole in my soul” I felt finally filled in my friend’s basement was nothing more than a flood of endorphins at last quenching destitute receptors. The heritable differences in endorphin signaling between those at low risk (left) and high risk (right) for alcohol abuse.

- In other words, addicts may be those who are especially charmed by the quality of carrots and immune to the beating of sticks, as any municipal court could attest.

- Never does nature say one thing and wisdom another. —Juvenal (Roman poet, A.D. 60–130)

- Until about ten seconds before the first time I used a needle, I thought I’d never inject drugs. Like most people, I associated needles with hard-core use. That is, until I was offered a shot.

Summary + Notes

As with every addict, my days of actually getting “high” were long past. My using was compulsive and aimed more at escaping reality than at getting off. I’d banged my head against the wall long enough to realize that nothing new was going to happen—except perhaps through the ultimate escape, death, which frankly didn’t seem like that big a deal.

This accomplishment would seem almost unremarkable to most addicts, who know firsthand that there is nothing we would not do, no sacrifice too great, to be able to use.

Addiction today is epidemic and catastrophic. If we are not victims ourselves, we all know someone struggling with a merciless compulsion to remodel experience by altering brain function. The personal and social consequences of this widespread and relentless urge are almost too large to grasp. In the United States, about 16 percent of the population twelve and older meet criteria for a substance use disorder, and about a quarter of all deaths are attributed to excessive drug use.

In purely financial terms, it costs more than five times as much as AIDS and twice as much as cancer. In the United States, this means that close to 10 percent of all health-care expenditures go toward prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of people suffering from addictive diseases, and the statistics are similarly frightening in most other Western cultures. Despite all this money and effort, successful recovery is no more likely than it was fifty years ago.

Although reliable estimates are hard to come by, most experts agree that no more than 10 percent of substance abusers can manage to stay clean for any appreciable time. As far as illnesses go, this rate is almost singularly low: one has about twice as good a chance of surviving brain cancer.

My aim in writing this book is to share these principles and thus shed light on the biological dead end that perpetuates substance use and abuse: namely, that there will never be enough drug, because the brain’s capacity to learn and adapt is basically infinite. What was once a normal state punctuated by periods of high, inexorably transforms to a state of desperation that is only temporarily subdued by drug.

“Alcohol makes you feel like you’re supposed to feel when you’re not drinking alcohol.” Among other things, I wondered why, if the drug can

The chief of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, George Koob, has said that there are two ways of becoming an alcoholic: either being born one or drinking a lot. Dr. Koob is not trying to be flip, and the high likelihood that one or the other of these applies to each of us helps explain why the disease is so prevalent. I agree that many who end up like me have a predisposition even before their first sip but also appreciate that enough exposure to any mind-altering drug will induce tolerance and dependence—hallmarks of addiction—in anyone with a nervous system. Unfortunately, though, no scientific model can yet explain my quick and brutal slide to homelessness, hopelessness, and utter desolation. Choosing

Until about ten seconds before the first time I used a needle, I thought I’d never inject drugs. Like most people, I associated needles with hard-core use. That is, until I was offered a shot.

All of us face countless choices, and there is no bright line separating good and bad, order and entropy, life and death. Perhaps as a result of following rules or conventions, some live under the delusion that they are innocent, safe, or deserving of their status as well-fed citizens. But if there is a devil, it lives inside each of us. One of my greatest assets is knowing that my primary enemy is not outside me, and for this I am grateful to all my experiences. We all have the capacity for wrong; otherwise we could not, in fact, be free.

The opposite of addiction, I have learned, is not sobriety but choice.

I’d finally reached the dead end where I felt I was incapable of living either with or without mind-altering substances. This bleak situation describes the condition of many, if not all, addicts and illustrates why relatively few recover. Despite being depleted, they think the cost of abstinence seems much too high: Without drugs, what is there to live for anyway? Eventually,

a willingness to take risks, and perseverance that make a bulldog seem laid-back have all contributed to the successes I’ve had as a neuroscientist.

Never does nature say one thing and wisdom another. —Juvenal (Roman poet, A.D. 60–130)

The idea that I am my brain still guides the efforts of thousands of neuroscientists around the world as we work to connect experience to neural structures, chemical interactions, and genes.

behavior. In fact, it’s beginning to seem that the brain is more like a stage for our life to be acted out upon than like the director behind a curtain calling shots. Nonetheless, it’s reasonable to assume that all of our thoughts, feelings, intentions, and behaviors at least have correlates in electrical and chemical signals in the brain, because there’s not a whit of evidence to suggest otherwise.

And the vast majority of us are trichromats, meaning that we perceive thousands of different colors by the combined activity in just three types of color-sensitive neurons. But some lucky individuals have a mutation that gives them a fourth type of color sensor, and even though they may not be aware of their mutant gift, they are more likely to have careers as artists or designers. The most important lesson here, though, is that our senses constrain our experience by offering us a relatively thin slice of what’s out there—a highly filtered version of our environment.

The fundamental role of the brain is to be a contrast detector. As experiences are distinguished from monotony, they spark neurochemical changes in specific brain circuits, informing us of all we care to know: opportunities for food, drink, or sex; danger or pain; beauty and pleasure, for example. The process of actively maintaining the stable baseline critical for conducting the brain’s business of contrast detection is called homeostasis, and it depends on having a set point, a comparator, and a mechanism for adjustment. It is easy to appreciate this principle in terms of body temperature, which is maintained around ninety-nine degrees Fahrenheit. If you become much warmer or colder than this, your body feels it, and there are mechanisms to return you to baseline, such as sweating or shivering. Feelings are also constrained within tight bounds under normal conditions. What we generally experience is our personal neutral okayness; otherwise we’d be incapable of detecting “good” or “bad” events.

All drugs affect multiple brain circuits, and variation in their sites of neural action accounts for their different effects. However, all addictive drugs are addictive precisely because they share the ability to stimulate the mesolimbic dopamine system. Countless studies have demonstrated that the squirt of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens from addictive substances (including chocolate and hot sauce!) is associated with the substances’ pleasurable outcome. Some, like cocaine and amphetamine, are universally effective; others seem to have a bigger influence on mesolimbic dopamine in some individuals than in others (for example, marijuana and alcohol), and some that have been labeled addictive probably aren’t. For instance, most research suggests that the psychedelic LSD does not stimulate the mesolimbic pathway. From this and related evidence, the majority of addiction researchers would argue that LSD is not an addictive drug.

pleasure. But in general, the mesolimbic pathway conveys a transient good time, not a stable sense of hopefulness

possible. Without dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, nothing, not a letter from a friend, an especially beautiful sunset or piece of music, or even chocolate,

recent years, new evidence has shown that dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway works not exactly by signaling pleasure but by signaling the anticipation of pleasure. This anticipatory state is not the same as the pleasure associated with satisfaction, contentment, or release, but rather the anxious, lip-smacking foretaste of something of import that is just around the corner.

or really valuable (oxygen to a deprived organism). In other words, this system alerts us to the anticipation of a meaningful event, not to pleasure per se. Pleasurable stimuli happen to be meaningful, but many other things are also inherently meaningful to an organism that has evolved to survive in ever-changing conditions.

Parkinsonian deficits occur between the desire to move and the movement circuitry, which are both intact.

Besides being slower to enact intentions, low dopamine is also associated with higher-than-average orderliness, conscientiousness, and frugality. In other words, it confers a tendency toward rigidity in areas other than movement.

To sum all this up, dopamine in the mesolimbic circuit leads us to appreciate opening doors, and dopamine in the nigrostriatal circuit enables us to do so. Drugs of abuse (as well as natural reinforcers like food and sex) stimulate both of these pathways, which is how drugs make us feel good and why we seek them.

Another aspect of our control over delivery is timing. Natural stimuli increase activity of the mesolimbic system by recruiting chemicals in a cascade of neural changes that come about gradually, generally after a few minutes. Drugs, on the other hand, are absorbed rapidly and act directly to produce nearly instantaneous changes in neurotransmitter levels, including dopamine. The difference is something like the slow bloom of dawn versus switching on a floodlight.

In general, the more predictable and frequent the dosing, the more addictive a drug will be.

The very definition of an addictive drug is one that stimulates the mesolimbic pathway, but there are three general axioms in psychopharmacology that also apply to all drugs: All drugs act by changing the rate of what is already going on. All drugs have side effects. The brain adapts to all drugs that affect it by counteracting the drug’s effects.

Exogenous (made outside the body) drugs often work this way because their shape sufficiently mimics endogenous

Repeated administration of any drug that influences brain activity leads the brain to adapt in order to compensate for the changes associated with the drug.

An addict doesn’t drink coffee because she is tired; she is tired because she drinks coffee. Regular drinkers don’t have cocktails in order to relax after a rough day; their day is filled with tension and anxiety because they drink so much. Heroin produces euphoria and blocks pain in a naive user, but addicts can’t kick a heroin habit, because without it they are in excruciating pain. The brain’s response to a drug is always to facilitate the opposite state; therefore, the only way for any regular user to feel normal is to take the drug. Getting high, if it occurs at all, is increasingly short-lived, and so the purpose of using is to stave off withdrawal.

Eventually, exposure to a favorite drug results in virtually no change in mesolimbic dopamine, but withholding it leads to a big drop, which we experience as a feeling of disappointment and craving. Thus the most profound law of drug use is this: there is no free lunch.

Having a set point enables meaningful interpretation of a stream of ceaselessly changing input. Sustained feelings in either direction impede our ability to perceive and thus respond to new information, so the nervous system imposes transience. This means that if something truly wonderful happens—you meet Prince or Princess Charming—the elation will not last. On the other hand, even the most terrible calamity won’t result in perpetual despair. This is also true with more mundane stimuli: we can probably all relate to the letdown after returning home from a great vacation, or to the flood of relief after a near accident on our commute.

While different people may have different set points, for any individual the neutral state is robustly maintained throughout life. Happy-go-lucky kids tend to be contented adults, and pessimists generally remain so whatever their circumstances.

Though for regular drug users affective stability makes it impossible to maintain a high, chronic use of stimulants like cocaine or methamphetamine may actually modify the affective set point. Unfortunately for users, this alteration is always in the “wrong” direction, resulting in lower baseline mood.

Persistent change in response to environmental input is called learning, and all organisms with a CNS—from cockroaches to the Dalai Lama—learn. As it turns out, memories, which are traces of learning, serve as Joe’s escape from the terror and tedium of his helpless consciousness in a hospital bed in Johnny Got His Gun. They are also, in

The term “tachyphylaxis” (TACKY-phil-axis), meaning “acute tolerance,” refers to the adaptive, compensatory changes that begin as soon as alcohol reaches the brain. A large and rather arcane literature surrounding tachyphylaxis has a practical implication that, were it widely known, might be a real boon to DUI defense lawyers and their clients. It turns out that there is a reliable and interesting twist in the relationship between blood alcohol level and impairment, due to tachyphylaxis. When

Virtually as soon as a drug begins to act on the brain, the brain begins to adapt—to counteract—that action. Thus, there is good rationale for arguing that despite a high BAC (blood alcohol concentration), because you are in a state of tachyphylaxis, you are really okay to drive. Good luck persuading the judge! In

If we are talking about drug use, we can think of the a process as what the drug does to the brain. Big doses produce large a processes, and protracted stimuli produce long-lasting a processes. But for each a process, there is a b process. The b process is the brain’s response to the a process, or the brain’s response to what the drug does to the brain, counteracting the changes in neural activity produced by the stimulus in an effort to return brain activity to its neutral, homeostatic state. When

While the a process is a direct reflection of the stimulus and so is always the same if the stimulus is the same (a certain number of ounces of alcohol or milligrams of heroin, for instance), this is not so with the compensatory b process. Generated by a powerfully adaptive nervous system, the b process learns with time and exposure. Repeated encounters with the stimulus result in faster, bigger, and longer-lasting b processes that are better able to maintain homeostasis in the face of disruption. Moreover, the b process can be elicited solely by environmental stimuli that promise the a process is coming—which is what happened with Pavlov’s dogs, who learned to salivate even when food was not present.

It also explains why the states of withdrawal and craving from any drug are always exactly opposite to the drug’s effects. If a drug makes you feel relaxed, withdrawal and craving are experienced as anxiety and tension. If a drug helps you wake up, adaptation includes lethargy; if it reduces pain sensations, suffering will be your lot.

My clever undergraduates are quick to point out a flip side to Solomon and Corbit’s model: if you want to achieve a sustained positive state, you could submit yourself to negatively charged experiences. This way the opponent process would be positive. Solomon and Corbit argued that such a pattern may be at work in an activity like skydiving. Jumping out of an airplane at several thousand feet produces intense feelings of arousal and panic, even feelings associated with impending death. They would probably last for much of the air time and certainly for all of the “free fall.” As the stimulus ends and your feet are miraculously back on solid ground, not only is the panic gone, but according to hobbyists it is like being awash in feelings of extreme calm and well-being. The relief following an intensely stressful experience, if you live through the event, may make it all worthwhile. Maybe this helps explain why people push themselves to exercise or go to graduate school.

The hallmarks of addiction—tolerance, withdrawal, and craving—are captured in the consequences of the b process. Tolerance occurs because more drug is needed to produce an a process capable of overcoming a stronger and stronger b process. Withdrawal happens because the b process outlasts the drug’s effects. And craving is virtually guaranteed because any environmental signal that has been associated with the drug can itself elicit a b process that can only be assuaged by indulging in the drug. This might happen at cocktail hour, during stressful times, or even upon awakening if that’s when you typically start using; in particular contexts such as bars or family gatherings; or in the presence of specific cues such as spoons, dealers, and paychecks, which is one of the reasons intense feelings of craving continue to frustrate recovery. To this day, and seemingly out of the blue, a certain warmth and humidity in the air or a specific type of music can make my mouth pucker with the anticipation of tequila.

Cutting-edge treatments take almost the opposite tact from the pastoral setting strategy (unless of course your using primarily took place on the farm). Following detox and some stability in mood and physiology (usually after several weeks of clean time), the addict is purposely exposed to cues that used to coincide with using, but this time within a supportive, therapeutic context. Wads of cash, drawing fluid into a syringe, or experiencing a disappointing day at first is likely to produce profound physiological and psychological effects such as changes in heart rate, body temperature, and mood. But with repeated exposure (and no drug delivery), such responses indicative of the b process begin to dissipate and eventually disappear. So, it is possible to extinguish a craving over time, as the brain adapts again, but this time to the non-predictive value of the cues.

Addiction differs in many ways from diseases typical of the broad category, a fact that took me several years to appreciate. Though I believed—and still do—that it is a brain disorder, it’s not like having a tumor or Alzheimer’s disease. Both of these can be definitively diagnosed by identifying particular cellular changes. Diabetes or high cholesterol is even easier to assess—by a simple blood test—and obesity is determined by a body mass index. On the other hand, there are no clear-cut tests to determine whether one is, or is not, an addict, and in addition to making diagnosis murky, this lack of clarity hinders efforts to cure the disease. If we remove the tumor or other errant structures, restore an appropriate insulin response, or lose enough weight, related diseases might indeed be cured. In the case of addiction—really a disorder of thought, emotion, and behavior resulting from widespread adaptation in multiple brain circuits—a cure is unlikely aside from removing most of the matter above my shoulders.

There are many contributors to this tendency toward excess, but ultimately my behavior is extreme because the stimuli (that is, drugs) have had such a potent impact on me relative to natural stimuli. The nervous system of an addict is acting normally and predictably in response to such consequential input, and addiction is a natural consequence. It’s also not likely to be prevented

The lackadaisical habits of so-called normal people who leave drinks half finished, snort a few lines on a Friday night, or occasionally smoke a cigarette with friends are strikingly different from those of addicts. Though adaptation still occurs in “chippers,” it is virtually imperceptible because of the irregular and low-dose patterns of use.

- The term “plasticity” is used by neuroscientists to refer to the ability of the brain to modify its structure and function. Though changes are always possible (that is, we remain somewhat plastic until the day we die), they are especially likely during periods of rapid development, until the age of about twenty-five years.

From the first time I got high until long after I’d smoked my last bowl, I loved marijuana like a best friend. This is not hyperbole. Some people it makes sleepy, others paranoid (due, no doubt, to an unfortunate confluence of neurobiology and genetics), but for me it was nearly perfect. One

If alcohol is a pharmacological sledgehammer and cocaine a laser (and they are), marijuana is a bucket of red paint. This is so for at least two reasons. First is its well-known ability to accentuate attributes of environmental stimuli: music is amazing, food delicious, jokes hilarious, colors rich, and so on. Second, its effects are neither precise nor specific, but modulatory and widespread. It’s a five-gallon bucket with a four-inch brush, painting up the gain on all kinds of neural processing.

It seems that anandamide and similar compounds evolved along with the CB1 receptor to modulate normal activity, highlighting important neurotransmission. The normal activity of the brain, as we’ve discussed, mediates all of our experiences, thoughts, behaviors, and emotions. The cannabinoid system helps to sort our experiences,

good. The millions of neurons involved in this discovery—including those involved in processing input from your senses, stimulating movement, coding memories or thoughts connecting this good thing to your plans or communicating it to others—are likely all releasing cannabinoids to turn up the volume on this information, helping to distinguish it from the other parts of your day in which interactions with the environment weren’t all that special.

This should make it easy to understand why the stimuli we encounter when stoned are so intensely rich. Sights, sounds, tastes, and thoughts that might otherwise be average take on incredible attributes. Early in my love affair with pot, I remember finding Rice-A-Roni so astoundingly delicious I couldn’t imagine how it stayed on the shelves of the grocery stores. Today I’d have to be backpacking for at least a week before I’d even find it palatable, but with my synapses primed for import, food is exceptional, music transcendent, concepts mind-blowing. What a wonderful treat

After I got sober, it took me a little over a year to go a single day without wishing for a drink, but it was more than nine years before my craving to get high abated. For the longest time, I couldn’t go to indoor concerts, especially if I was in proximity to pot. Good sinsemilla would induce a sort of mini panic attack. I’d

Predictably, chronic exposure leads to substantial consequences. The brain adapts by downregulating the cannabinoid system.2 “Downregulation” is a general term describing processes that work to ensure homeostasis, which in this case translates to a dramatic reduction in the number and sensitivity of CB1 receptors. Without copious amounts of pot on board, everything is dull and uninspiring.

There’s been a long-standing debate, akin to one about the relationship between cancer and smoking in many ways, about whether regular marijuana smoking leads to an amotivational syndrome (“amotivational” means lacking motivation). For instance, does regular use lead to spending long hours on the couch watching cartoons, or does it just so happen that people who like to sit around watching television (or poring through shells at the beach) also enjoy marijuana? Because correlation doesn’t mean causation, cigarette companies argued for decades that a predisposition for cancer and the tendency to inhale cigarette smoke just coincidentally occur in the same people. In both cases, common sense and mounting evidence point to the same thing. Downregulation of CB1 receptors might make the user more suitable for jobs that don’t require creativity or innovation, exactly the effects that initial exposure seemed to stimulate.

“Great,” I said. “How’s it with your kids when you’re not high?” “Increasingly irritating and tedious,” he admitted.

So, if you smoke weed, remember that infrequent and intermittent use is the best way to prevent downregulation and its unfortunate effects: tolerance, dependence, and a loss of interest in the unenhanced world.

Unlike stimulants, or even alcohol, the subjective effects of these drugs seem almost perfectly subtle as they bestow utter contentment.

Among women, who are most likely to take these medications (partly because they are more likely to suffer from chronic pain), the first decade of the twenty-first century saw a 400 percent increase in lethal overdoses.

The drive to change our subjective experience is universal, and there are many like me who will try anything that might get us high. Therefore, the solution is not to be found on the supply side, but rather depends on a change in demand, and that’s likely to be an inside job.

The patients recognized in their friend’s death a sign of high-quality dope. You’ve probably seen similar phenomena in your community; regional bursts in overdoses tend to occur not because most addicts don’t know what’s to be found but because they do. They are victims of the laws of pharmacology who fail to recognize that even drugs like fentanyl and carfentanil, which are thousands of times as potent as heroin, can’t deliver the desired effects to a learned brain (though, unfortunately, they remain potent enough at depressing respiration, which is how they can be lethal). Dream

Stimulants increase activity, hallucinogens alter perception, and sedative-hypnotics slow brain activity and promote sleep.

From a neuroscience perspective, the appeal of opiate drugs is easy to understand. The large class of narcotics, from heroin, fentanyl, and oxycodone to their less potent analogs like tramadol and codeine, all work by mimicking endorphins (endogenous morphine-like substances), the body’s natural painkillers. It turns out that our brains manufacture an incredibly rich and varied pharmacopoeia of these natural opioids, the sheer number and wide distribution of which suggest that they play a critical role in our survival.

Suppose you are overcome with pain and fear and spend what remains of your life writhing on the floor of your apartment until you bleed to death or are dispatched some other way. This is unlikely to help you survive or—more to the point—reproduce in the future. Instead, within about ninety seconds of the alarming encounter, cells in your brain will stimulate gene activity to direct the synthesis of endorphins, which are quickly released to produce effects throughout the central nervous system: blocking pain transmission, inhibiting the panic response, and hopefully facilitating an escape. It is easy to see how modulating pain and suffering would provide evolutionary advantage to an organism.

There are dozens of different opioids manufactured by the brain (including actual morphine). Experiments have shown that these chemicals serve a range of critical functions including modulating activities like sex, attachment, and learning.

These have been collectively called anti-opiates, and they produce exactly the opposite effects as narcotics. Why did evolution or that benevolent Creator decide we need compounds that enhance suffering and restlessness?

Once you are no longer in immediate danger, it would actually be helpful to perceive your pain rather than to remain analgesic. Otherwise you might still die—just more slowly—from loss of blood or, eventually, infection. So the brain doesn’t wait for the endorphins to naturally degrade. Instead, the edges of perception are sharpened by a flood of anti-opiates. In fact, pain has two primary purposes: the first is to teach us to avoid dangerous stimuli or situations, and the second is to encourage recuperation after failing the first lesson. Another potential rationale for the existence of anti-opiates was outlined in earlier chapters: the brain’s role as contrast detector relies upon a stable baseline. Anti-opiates restore the brain to its baseline most efficiently. One

But if a drug makes your mouth water, the cues associated with the drug would give you cotton mouth instead. This apparent contradiction is understood by appreciating whether or not a stimulus acts directly on the CNS and recruits homeostatic processes. A drug does. Dinner does not.

But the anti-opiate system is the cruelest. Because an addict’s nervous system is regularly flooded with compounds that produce euphoria, the anti-opiate system ramps up to create pain so that the net effect is something like normal sensation. This opposing anti-opiate system can be turned on by safety, or by the expectation of safety after danger passes, but it’s likely that there is no more effective way to activate anti-opiate processes than through regular exposure to opiates, which must

Adaptations that underlie opiate addiction, including the production of anti-opiates, begin during the very first administration (this is true of all drugs) and rapidly gain strength with use. The strength of these opponent processes may be so robust because the sensation of pain is so critical for survival.

Addicts can administer upwards of 150 times the dose that would be lethal to naive users and, even so, just feel “right” but not really high. In

Methadone acts as a substitute opiate—one that is orally absorbed and has an especially long half-life. Drinking a daily “cocktail” at the clinic prevents withdrawal (as well as antisocial activities that help keep withdrawal at bay, like stealing and shooting up in public places), and because the drug is so cheap, it’s been seen as of great benefit—though likely less to the addicts than to members of their communities.

A better strategy from a neurological perspective might be to employ the opposite tack. Instead of bathing the cells in opiates for long periods, knock them over the head with a big dose of anti-opiates! Giving anti-opiates should induce the brain to maintain homeostasis by upregulating, or at least normalizing, its opioid system. This has in fact been tried and in some ways works like a charm. Here’s how it goes: you check into a hospital, receive general anesthesia (the reason for this will be clear momentarily), and take a whopping dose of Narcan. This drug occupies all of the same sites opiates do but doesn’t activate them. If Narcan is administered to unsedated addicts who haven’t been using, they will come unglued—instantaneously experiencing the throes of withdrawal. However, if they are anesthetized while their brain is bathed with high doses of the drug, then the cells adapt back to their naive state in fairly short order.

Suboxone is a combination of a Narcan-like drug and an opiate drug called buprenorphine. Buprenorphine doesn’t have much street appeal for the same reason it’s a good choice here: although it occupies the same places in the brain as opiate drugs, it doesn’t do as good a job and therefore it is much less rewarding than its abused counterparts. However, the effects are potent enough to reduce symptoms of withdrawal, including craving, and to allow addicts to sleep. It’s less stigmatizing than methadone, but even more important, under a doctor’s supervision, it won’t make the addiction stronger. For someone motivated to get clean, this could provide a sound start. If the dose is tapered over time, it’s likely to afford the best shot at a life free from opiate addiction.

This custom certainly hasn’t diminished in the past couple of centuries, and it presents a tremendous challenge to recovery.

The manic insistence on ignoring the obvious is reminiscent of cigarette commercials I grew up watching. The juxtaposition of youthful athleticism with a nicotine habit seemed as odd to me as a child as the insistence today that alcohol somehow makes everything sexier and livelier. I still remember one commercial in particular that showed a group of gorgeously tanned young adults whitewater rafting down a rugged canyon as they promoted a popular menthol brand. Really? Smoking while rafting?

True, at times life can be awful, disappointing, terrifying, or mind-numbingly tedious. But just the same, there is the frequent possibility of being overcome with joy, gratitude, or delight. In short, it is likely impossible to tamp down terror without also leveling pleasure. As Socrates noted, and many appreciate, sorrow and joy depend on each other; I prefer the roller coaster to the train.

People also take drugs in order to reduce unpleasant feelings. This tendency is called negative reinforcement, and the motivation it provides is critical. Alcohol and other downers are negatively reinforcing in part because they reduce anxiety; opiates are so compelling because they reduce suffering; stimulants because they reduce boredom. Moreover, because alcohol reduces anxiety, this drug will be more reinforcing to those who are naturally anxious than to those who are not, increasing the risk of regular drinking in such individuals. There is good evidence that those of us who are naturally inclined toward any of these predisposing states are more likely to abuse the “complementary” substance.

However, because the brain adapts to the neural changes wrought by any drug, the effects of chronic exposure are going to undermine any attempts at self-medication. Alas, if someone finds alcohol especially rewarding because of an inherited tendency toward anxiety and she imbibes frequently, she’ll become

Other people have deficiencies in the primary enzyme that is responsible for metabolizing nicotine, and for these smokers the concentration of the drug in the blood gets higher and stays high longer. Because too much of this drug is also unpleasant, these people are less likely to smoke, and when they do, they are more likely to successfully quit. Chalk one up for positive punishment.

In other words, addicts may be those who are especially charmed by the quality of carrots and immune to the beating of sticks, as any municipal court could attest.

Because the process of fermentation is so simple, it has been discovered and exploited by virtually every human culture.

Paradoxically, the simplicity of the ethanol molecule is what makes it so difficult to understand. Molecules of cocaine, THC, heroin, and ecstasy are much larger and more structurally complex, and therefore their sites of action in the brain are very specific. Alcohol is so small and wily its actions are hard to pin down. It’s easy to imagine that there are many more places to park a skateboard than an airplane. Because the effect of a drug is dependent on this “parking” or “binding,” and alcohol does this at multiple sites, its effects are also much less specific.

Cocaine blocks a protein that recycles dopamine, and because dopamine hangs around longer than usual, we feel euphoric and energized. For alcohol, the target(s) are not as clear, which is to say that the mechanisms of drunkenness are still being worked out.

Alcohol also reduces activity at glutamate receptors. Glutamate happens to be the primary excitatory neurotransmitter, so this plus GABA inhibition really tamps down the electrical activity of neurons. Glutamate is also critical for forming new memories, and if I had blacked out that day (that is, forgotten chunks of experience), it likely would have been from alcohol’s ability to impede glutamate’s activity. Because glutamate and GABA are so prevalent, alcohol slows neural activity throughout the brain, not just in a few pathways, explaining the drug’s global effects on cognition, emotion, memory, and movement.

We have long known that alcohol use rapidly leads to the synthesis and release of beta-endorphin, a string of thirty-one amino acids that is thought to contribute to the drug’s euphoric and relaxing effects by increasing mesolimbic dopamine levels and inhibiting the “fight or flight” response. This system is the target of one of the pharmaceutical strategies to combat alcohol abuse, naltrexone, a longer-acting and orally available cousin of naloxone, which is marketed as Narcan. Both naltrexone and naloxone firmly park on opioid receptors but don’t activate them. (Thus they are called opioid antagonists.) Naltrexone, marketed as ReVia and Vivitrol, occupies these sites for relatively long periods so that when a person drinks alcohol, any endorphin activity is rendered moot. Narcan/naloxone doesn’t hang around as long but effectively reverses an opiate overdose by fitting even better than opiates do into the “parking” spot and therefore kicking them out.

Data such as these suggest that some of us are especially likely to find alcohol reinforcing because we can use it to medicate an innate opioid deficiency. Perhaps the “hole in my soul” I felt finally filled in my friend’s basement was nothing more than a flood of endorphins at last quenching destitute receptors. The heritable differences in endorphin signaling between those at low risk (left) and high risk (right) for alcohol abuse.

As the concentration in the blood and brain increases, judgment is impaired and motor skills decline while risky behavior increases, along with memory and concentration problems, emotional volatility, loss of coordination, including slurred speech, and confusion. Finally, nausea rises and vomiting begins as the area postrema, otherwise known as the brain’s vomit center, reflexively works to expel the poison. Eventually, the drinker could fall into a coma. If intoxication occurs very rapidly—for instance, by guzzling high-potency beverages on an empty stomach—it’s possible for the anesthetic effects to occur before the vomit reflex is engaged. In this case, as the brain is shut down, it’s possible to die from overdose.

Binge drinking is risky for anyone, but particularly for those whose brains are still developing. The impact of high alcohol concentrations during this “plastic” period leads to lasting alterations in brain structure and function and is more likely to result in an alcohol use disorder. The converse is also true: one of the most effective ways to curtail the risk of addiction is to avoid intoxication during periods of rapid brain development. People who begin drinking in their early teens, as I did, are at least four times more likely to eventually meet the criteria for an alcohol use disorder. In fact, the lifetime risk for substance abuse and dependence decreases about 5 percent with each additional year between ages thirteen and twenty-one.8 Yet young people are especially prone to binge drinking in part because they are neurobiologically primed to seek and appreciate novel and high-risk experiences. Though their parents may not appreciate it, for adolescents these tendencies are well timed to promote the development of adult goals and identity formation.

Lower blood volume and slower metabolism may also partly explain the steeper dive in women alcoholics who more quickly progress to organ damage, disordered use, and death from drinking.

As a rule, sedation is not as much enjoyed as stimulation, which is why, despite its popularity, alcohol is not as addictive as are some other drugs. Over 85 percent of the world’s adults drink, but only about one-tenth of these develop a problem. Also, even though the ethanol in all alcoholic beverages is the same molecule, different beverages contain different congeners or impurities from the distillation process, often connected to the source—tequila has more congeners than vodka—that can affect the experience of intoxication and withdrawal

While the consequences have generally gotten stricter, the per capita consumption both here and worldwide has been rising fairly steeply since my heyday. Excessive use of alcohol now results in about 3.3 million deaths around the world each year.9 In Russia and its former satellite states, one in five male deaths is caused by drinking. And in the United States during the period between 2006 and 2010, excessive alcohol use was responsible for close to 90,000 deaths a year, including one in ten deaths among adults aged twenty to sixty-four, translating to 2.5 million years of potential life lost. More than half of these deaths and three-quarters of the years of potential life lost were due to binge drinking.

In fact, alcohol killed about twice as many people in 2016 as prescription opioids and heroin overdoses combined, and even this number would be almost three times higher if it included drunk-driving-related deaths.

place. For example, by the 1970s, Valium was the single most prescribed brand of medicine in the United States, used by about one in five women.

In 2013, close to 6 percent of U.S. adults filled more than thirteen million prescriptions for sedative-hypnotics.

The first true sleep medicine was chloral hydrate, perhaps familiar to some as the knockout drops mixed with alcohol to make a Mickey Finn. A

“hypnotic” refers to their sleep-inducing properties. Because

Unfortunately, the problem with all the drugs that have been developed to treat these serious issues thus far is that with regular use they elicit an opponent process, therefore creating the state they were designed to remedy. The insomniac become sleepless. The anxious become wrecks.

What I liked most about the downer class was the feeling of distance from my feelings.

Or we might speculate that the decline in the use of tranquilizers, caused mostly by negative press and pressure on doctors to reduce the number of prescriptions written, was related to the rise of alcohol use. It would be no wonder, because these drugs essentially represent alcohol in pill form.

Americans changed the name to barbital in a sleight of hand during World War I to permit manufacture of German products in the United States without having to pay royalties.

More recently, Michael Jackson succumbed to a massive dose of Propofol, which his private doctor administered to help him sleep. The very short-acting anesthetic doesn’t share the barbiturate structure, but acts in a similar fashion. It’s a very good anesthetic because it has a really fast onset and short half-life, but like all these drugs, as well as the rest of Mr. Jackson’s pharmacological strategies, doses need to escalate as tolerance develops, making the therapeutic window grow narrower and the risk of accidental overdose grow greater over time.

Speaking of which, both inventors of barbiturates, the chemists Fischer and von Mering, died of overdose after years of dependence.

Not surprisingly, those claims were overstated. Millions of people are now hooked on benzos, but on the bright side it’s not possible to overdose from them alone, so the market is likely to stay strong.

example, whether or not you are able to drink others under the table, or are known as a “lightweight,” has been attributed to the particular makeup of subunits. Structural differences may also confer individual variation in pain sensitivity, anxiety, premenstrual or postpartum depression, diagnosis on the autism

The major difference between benzos and barbiturates is that overdose is virtually impossible with benzodiazepines alone and fairly likely with barbiturates.

Excessive anxiety is estimated to be the sixth leading cause of disability across the globe.5 Anxiety differs from fear in that the latter is an emotional response to a clear and current danger, as opposed to apprehension about possible future events or unfocused or irrational worry. There are many ways anxiety disorders are expressed, including panic disorder, phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). Anxiety disorders are also linked to depression; these are sometimes thought of as two sides of the same underlying issue(s). Anxiety disorders tend to begin early in life and follow a recurrent, intermittent course, exacting costs on life satisfaction, income, education, and relationships.

In fact, women tend to be two to three times more susceptible to all stress-related disorders, at least partly as a result of neurobiology that is only beginning to be investigated.

The difference between those with ADHD diagnoses and those without is quantitative: for those with the disorder, drug treatment brings their cognition within normal range.

Multiple studies have shown that when these substances are administered in a controlled laboratory setting, virtually everybody enjoys their effects.

other drug effects, including those associated with movement and cognition, tend to get more robust rather than less so with repeated exposures, a phenomenon called sensitization. Sensitization among stimulant users is thought to account for bizarre behavioral and cognitive changes that often develop over time, such as stereotypy. Stereotypy is evident as highly dosed or sensitized individuals engage in purposeless, repetitive movement. There can be other causes of stereotypical behavior besides drugs, but it is common enough among speed users to have its own slang: users often refer to stereotypies as punding or tweaking, as they mindlessly sort, clean, or dis- and reassemble objects,

In fact, there are several documented benefits to regular caffeine use including improvements in mood, memory, alertness, and physical and cognitive performance. It also seems to reduce the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease and type 2 diabetes. This is all good news, especially because, unlike many other psychoactive substances, it is legal and unregulated nearly everywhere.

over 1.1 billion people smoke tobacco, and more than 7 million die each year from their addiction. Like

Though I’m also a former smoker and can therefore be self-righteous, I don’t think nicotine is worth dying for. On average, tobacco users lose fifteen years of life.

In fact, the total annual cost of smoking is almost 2 percent of global gross domestic product, which is also about 40 percent of what all the world’s governments spent on education.

Once in the lungs, it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream and distributed to the brain in about seven seconds. (A pack a day smoker takes in over two hundred separate hits of nicotine a day.)

As with all drug addictions, the target concentration is an ideal window between withdrawal and toxicity. Nicotine is metabolized fairly quickly, and a smoker has to regularly dose to avoid withdrawal,

The dynamic adaptations that lead to tolerance within such a short time are mirrored on the other end as tolerance partially decreases during even a few hours of withdrawal, so the first few puffs are the best of the day. The bigger lesson here is the temporal symmetry: tolerance that develops rapidly tends to reverse quickly too, while changes that take longer to accrue tend to persist.

Some of these effects have led to the idea that a nicotine patch might be used to treat cognitive decline in the elderly—the drug can improve some aspects of attention and memory—but the unlikelihood of being able to take anything long term without incurring compensatory adaptations, or substantial side effects, has so far kept these out of the clinic.

Many people notice that drinking makes them want to smoke, or vice versa, and wonder why this is. There are several hypotheses, each of which may explain part of the relationship. For one, any drug that stimulates dopamine greases the rails for another. Because they are both addictive, they can also serve as reminders of addiction, and especially when smoking was okay in bars, the contextual cues were largely overlapping. Also, the arousing effects of nicotine may counteract the sedative effects of alcohol, reflecting the familiar pattern of users counterbalancing uppers and downers. One more hypothesis suggests that smokers can drink more, perhaps because nicotine stimulates digestion and this might decrease alcohol absorption from the gut. So, until further study, we’re not sure whether, overall, the two drugs enhance or counteract each other’s effects.

My relationship with cocaine was more like leaving a mean, unfaithful lover. Pangs of desperate regret mixed with a growing sense of relief. It was like most users of coke and meth in that my compulsion was repulsive even to me, yet I’d have kept on, grinding my jaw tighter, had it not been for Steve’s brief epiphany that probably saved my life. He was the friend who noted with unexpected insight that there wasn’t enough cocaine in the world to satisfy our desire, and somehow—I honestly have no idea how—steered us both away from injecting over the ensuing several months that it took me to get to treatment.

Cocaine is like the sole porn shop in a down-and-out town. You hate yourself for going but end up visiting over and over. While using, especially in a binge, I felt as if I were flooring the gas pedal, headed for a granite wall, unable or unwilling to stop, or even to care. It was the short course to self-loathing, and with every bag my soul grew more and more hollow. Cocaine is the drug I miss the least.

does not involve interacting with a receptor. Instead, they interfere with the recycling mechanism for monoamine neurotransmitters. Though the name monoamine might be new, most people are familiar with the members of this group of neurotransmitters: dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine (or adrenaline), serotonin, and melatonin, chemicals that play major roles in mood and sleep.

Coke, speed, and E all act by blocking transporters. Transporters, like receptors, are proteins embedded in the neural cell membrane, but unlike receptors the function of transporters is to transport (or recycle) released neurotransmitter back into the presynaptic neuron, where it can be repackaged and reused. Transporters are one of the two main ways that synaptic transmission is discontinued; the other is through enzymatic degradation. Without transporters or enzymes to break apart neurotransmitters, synaptic transmission would persist much longer than it does, and therefore the signal would be quite different. When one of these drugs occupies a spot on a transporter, it prevents the monoamines from utilizing their reuptake mechanism and prolongs their effects. In the case of dopamine, for example, indication of something newsworthy would be more like a home alarm than a pop-up notification.

Thousands of people have lost their families, jobs, homes, and lives because the ability of cocaine to extend dopamine’s presence in the synapse seemed worth giving up relatively unimportant stimuli like relationships, a livelihood, and teeth. The half-life is very short (usually less than an hour), and though pharmacologists say the subjective effects last about thirty minutes, in my experience it was more like three, barely enough time to prepare the next bump.

Methamphetamine abuse is a significant problem worldwide. Though rates in the United States have been stable with about a million chronic users, the market is growing quickly in East and Southeast Asia.8 Meth is a Schedule II drug and may be prescribed for ADHD, extreme obesity, and narcolepsy, but amphetamine is more often the choice of physicians because it is less reinforcing than methamphetamine (the addition of a methyl group increases absorption and distribution). Either of these drugs can be neurotoxic when taken at high doses, and there is no treatment for this brain damage.

when all three superpowers (Japan, Germany, and the United States) might have been so as a result of loading their troops with “uppers.”

The half-life of methamphetamine is about ten hours (ten times that of cocaine), but amphetamine’s half-life varies widely—anywhere from seven to thirty hours, depending on the pH of the user’s urine.

In contrast to most other drugs, where there is more or less a linear relationship between time since last using and the experience of craving, with coke and meth craving seems to build over time, and most users relapse within a few weeks.

the way a hungry lab rat must

(As a rule of thumb, it takes about five half-lives to get rid of about 95 percent of any drug, so this one hangs around for a couple of days.)

But for many, the acute effects make this short-term dip well worth a little low. The drug greatly enhances a sense of well-being and produces extroversion and feelings of happiness and closeness to others, due in part to the fact that it impairs recognition of negative emotions, including sadness, anger, and fear. Affective neuroscience (the study of the brain’s role in moods and feelings) has demonstrated quite clearly that we can’t feel what we can’t recognize, so this pro-social bias seems perfectly engineered and helps explain why ecstasy is called the love drug and has been adopted for use by marriage counselors. In terms of unpleasant acute effects, the drug can cause overheating, teeth grinding, muscle stiffness, lack of appetite, and restless legs—none of which are especially contraindicated on a dance floor. At

But, alas, the more you take any drug, the larger the b process grows, and the opponent/dark side of this drug is truly awful. Many regular users look to be headed for a lifetime of depression and anxiety.

For example, primates given ecstasy twice a day for four days (eight total doses) show reductions in the number of serotonergic neurons seven years later.

There were two major findings. First, former and current ecstasy users were virtually identical, and, second, these groups showed significantly more clinically relevant levels of depression, impulsiveness, poor sleep, and memory impairment. Again, these were recreational users, many had not taken the drug for years, and still deficits were strikingly evident.

As discussed, coke, meth, and E interact not with receptors but with transporters, but that in itself is not what makes them dangerous. Indeed, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as well as older tricyclic antidepressants are some of the most well-known transporter-blocking drugs, and neither shows evidence of permanent brain damage. Even cocaine doesn’t appear to cause the same sort of long-term damage that amphetamines and ecstasy do, perhaps because it—like the antidepressants—stays in the synaptic gap rather than being transported into cells like its more toxic cousins. It seems likely that the presence of these drugs inside the

A singular fact about psychedelics is that the majority of scientists who study abused substances don’t think these are addictive.

Psilocybin, mescaline, and DMT are natural compounds that have been used for millennia by indigenous people in sacred rituals; LSD is a synthetic compound, created by Albert Hofmann, a Swiss chemist, in 1938.

and who often bring nothing to the experience but a vacuous yearning.

the very body of the Western heritage at best, in favor of exotic traditions they only marginally understand; at worst, in favor of an introspective chaos in which the seventeen or eighteen years

usually delivered through a paper tab that has been dosed with a small amount of liquid, will induce a trip that lasts for six to twelve hours. Mescaline is similarly long acting, while psilocybin’s duration is about half as long. All of these are typically taken orally and induce rapid and profound tolerance. In fact, besides the fact that they don’t cause dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens, this tolerance is so quick that regular use is pointless.

The first time I tripped, and every time after, was like opening a door into a much more vast and mysterious existence than the one I usually inhabited.

worthwhile. My good fortune was probably partly due to my optimistic constitution and the somewhat idiotic naïveté that characterized the 1980s.

because deep down I knew my smoking was mostly to quell the panic and boredom of not smoking—I

These drugs don’t lead to the release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens (need I say more?), so nonhuman animals won’t self-administer them.

For instance, khat is so popular in Yemen that its cultivation consumes an estimated 40 percent of the country’s water supply.

In addition to this sense of detachment, sometimes accompanied by a feeling of leaving one’s body, the drugs produce amnesia, so whatever happens under their influence is lost to conscious memory.

addition, at least some of PCP’s effects are due to increased levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate, and excess glutamate has also been implicated in schizophrenia. The

Unfortunately for them, chronic use is bad for the brain. Reflecting the ubiquitous role of glutamate signaling, a variety of negative effects are evident in regular users, supported by parallel research in other animals, including problems with incontinence, cognitive deficits, gross abnormalities in brain structure, deficits in dopamine signaling, and a loss of both dopamine and glutamate synapses. Because these drugs are still used in the clinic, there is some concern, especially regarding pediatric anesthesia, that they may be altering brain structure and function, although studies in humans are so far inconclusive.2 Unwittingly,

There is a well-established positive correlation between exposure to weed or other natural cannabinoids and a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The general consensus has been that cannabinoids don’t cause the disorder but can unmask a latent vulnerability, bringing schizophrenic symptoms to the surface that might otherwise have remained below the threshold for detection.

drop in the number of functional CB1 receptors. In such cases, users can expect profound cross-tolerance so that smoking weed would actually be about as effective as smoking the grass in your backyard.

Although inhalant abuse exists worldwide, it’s especially common among the poor and the homeless, including especially children who work or live on the street.

The effects of inhalants are similar to getting drunk, but some people report experiencing something like hallucinations. A sudden sniffing death syndrome may occur, but more commonly these compounds tend to damage the liver, kidneys, lungs, and bone in addition to the brain. Repeated use has been linked to cognitive impairment, likely due to degeneration of neural pathways as the axons that conduct information throughout the brain lose function, and perhaps to lead poisoning from huffing gasoline.

Schedule I or II substances were made illegal by analogy. The need for this law was so compellingly obvious, even to Congress, that it was introduced, passed by both houses, and signed by the president of the United States (Reagan) in less than two months. However, like virtually all legal attempts to control the drive to use drugs, it hasn’t made a dent.

one of those people who couldn’t control their use. I thought I was smarter…or more resolute…or more deserving. Besides, I was just getting started and way too young to have a habit. My desperate evasions were just like those of millions of other people determined that they’d never be like a drunkard parent or

Sure, I met some of the criteria some of the time, but my ability to fool teachers, clinicians, and law enforcement stemmed from an ability to fool myself.

say there are four primary reasons people like me develop addictions. Well, actually five, but I’m saving the gloomy news for last. The four are these: an inherited biological disposition, copious drug exposure, particularly during adolescence, and a catalyzing environment. It’s not necessary to have all four, but once some threshold is reached, it’s like breaching a dam—virtually impossible to rebuild. So, with enough exposure to any addictive drug, any one of us will develop the hallmarks of addiction: tolerance, dependence, and craving. But if the biological predisposition is very high, or use starts during adolescence, or certain risk factors are present, less exposure will do the trick. Genetics

for instance, some people might have a tendency toward anxiety or be naturally endorphin deficient, and both of these states can be remedied by drinking.

All genetic influence, we’ve learned, is context dependent and incredibly complex.

The relatively new field of epigenetics is just getting under way, but it is thought that some of our parents’ and grandparents’ experiences are imprinted in our cells this

other words, the experiment suggested that if your parent used THC before you were conceived, you may be at increased risk

It’s increasingly looking as if exposure to drugs of abuse in our parents and grandparents predisposes us to take drugs ourselves—effectively a b process across generations.

concretized by lasting patterns in the brain and behavior. The downside of this is that any neurobiological consequences of drug use are much more profound and longer lasting when exposure occurs during adolescence than when it occurs after about age twenty-five—the neural definition of adulthood.

Beyond the gateway effect, we know that chronic THC users have an increased tendency to feel blue, show more difficulty with complex reasoning, and suffer from things like anxiety, depression, and social problems. Scientists

The heart of the matter is that the brain adapts to any drug that alters its activity and it appears to do this permanently when exposure occurs during development. The more exposure to the substance we have, and the earlier we have it, the more strongly the brain adjusts.

Those with high anxiety—whether they got there from inherited liabilities or stressful experiences, or both—are obviously more likely to enjoy the benefits of sedatives like alcohol and benzodiazepines.

Even today, I’m confounded by people who can drink or use other drugs but don’t. For me, and others like me, nothing short of impending doom (and often even that) would provide enough incentive to forgo pharmacological stimulation. People who stop after only one drink, mete out cocaine like a banker, or keep a bag of weed around for months are entirely foreign to my experience and beyond my capacity to comprehend.

For example, on some reservations close to half of children are born with fetal alcohol poisoning, and rates of addiction are similarly through the roof.

However, no biological differences have been discovered that explain the higher rate of addiction in these people.

The more closely we examine any aspect of reality, the more we see how much there is to learn. Complexity,

As a result of looking closely at any problem, we increasingly realize the flaws in our assumptions and ask better and better questions. So, I can say with absolute certainty that there’s not “a gene” for addiction, nor is it caused by a “moral weakness”; it doesn’t “skip a generation”; all people aren’t equally vulnerable, nor is any one person equally at risk across the life span. In other words, we know a lot about the causes of addiction, and they are complicated.

but “how much more likely am I” to become an alcoholic if my parent or grandparent lost control of his or her drinking than if no one in my immediate family had done so? The answer is about 40 and 20 percent, respectively, versus 5 percent. In

It turns out that we have about half the number of genes as the average potato: around twenty thousand!

The truth is, people like me who are prone to excessive use are less likely than average to be swayed by outside pressure, including punishment. We’re also more likely to ignore public mores

it’s been done with Suboxone/buprenorphine for opiate addicts, with Chantix/varenicline for smokers, and with benzos for alcoholics, to a lesser degree, because the drug is such a generalist.

fact, there is no evidence of addiction among people who use coca in its indigenous form. Risk for addiction likewise increased with distillation of alcohol—yielding concentrations way above the limits of fermentation. And so on. As drugs get more potent, they are easier to traffic, and once they are popular, it’s a pretty good bet that synthetic versions—with even more potency—are on their way.

After being sober for some time, I was stopped at a light early one morning on Spanish River Boulevard in Boca Raton. Glancing over at the car next to me, I noticed a seemingly normal fellow guzzling from a bottle in a brown paper bag. He looked up, and our eyes connected over the edge of the bag. What has haunted me ever since is how thoroughly and quickly I looked away, as if I had done something wrong by noticing his early-morning nip. And I did feel, and can still recollect, a sense of shame and, I’m embarrassed to say, distaste. Why do people who are acting so contrary to their own best interests evoke denial in all of us? A victim of virtually any disease usually elicits pity; addicts mostly evoke revulsion. What is it about the irrational behavior of an addict that makes everyone want to turn away?

and behavior, in ways that are direct and profound. As we grapple to respond to the growing population of addicts, we’d do well to recognize that disordered use comes from, thrives in, and creates alienation. This means that building walls to keep us from our emotions or our neighbors will only make things worse, by feeding the epidemic.

-

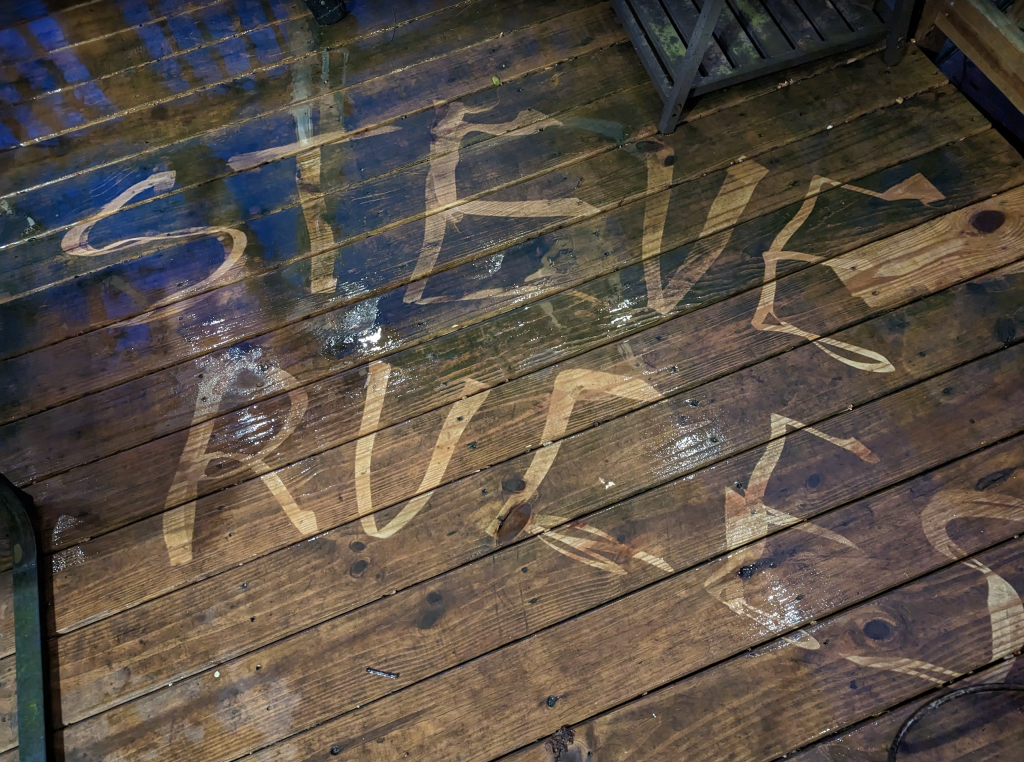

Seen on a walk

-

Mine Were of Trouble by Peter Kemp

From my Notion Template

The Book in 3 Sentences

- A somewhat erratic memoir of a Nationalist volunteer in the Spanish Civil War. It doubles as something of a war travelogue, and has the general air of a tourist on a very gripping vacation trip, with grenades, death and maiming. It was seemingly written before they invented trauma in literature, or at least written by an author not able to write it.

How I Discovered It

The Amazon Algorithm.

Who Should Read It?

Anyone who enjoyed Storm of Steel by Ernst Junger – it’s not as good and could have used an editor, but good nonetheless.

How the Book Changed Me

How my life / behaviour / thoughts / ideas have changed as a result of reading the book.

I’m not sure I was changed in any way, but seeing the very, very wide range of human experience is always interesting – particularly how Kemp could just turn the war on an off (rational, since he was a tourist/volunteer) whereas the Spanish on either side could not

My Top 3 Quotes

- The details of his flight had been arranged in London by a certain Major Hugh Pollard, one of those romantic Englishmen who specialize in other countries’ revolutions.

- Father Vicente, in great spirits, dominated the gathering. He was the most fearless and the most bloodthirsty man I ever met in Spain; he would, I think, have made a better soldier than priest.

- The motto of the Legion was ‘Viva la muerte!’

Summary + Notes

Of course, if I had been willing to join the International Brigade and fight for the Republicans it would have been simple; in every country there were organizations, ably directed by the various Communist parties, for that very purpose. But

Certainly the execution of prisoners was one of the ugliest aspects of the Civil War, and both sides were guilty of it in the early months. There were two main reasons for this: first, the belief, firmly held by each side, that the others were traitors to their country and enemies of humanity who fully deserved death; secondly, the fear of each side that unless they exterminated their adversaries these would rise again and destroy them.

Resolved to be the first to welcome the victorious army, he and a Spanish friend of a similar temperament, Ricardo González, of the famous sherry family, loaded his aircraft with crates of sherry and brandy, took off from San Sebastian and soon afterwards landed on the airfield at Santander. A swarm of blue-clad soldiers surrounded the aircraft and Bellville and González climbed out with glad shouts of ‘Viva Franco!’ and ‘Arriba España!’ when they realized with astonishment and dismay that these were Republican militiamen and that Santander was still in enemy hands. They were brusquely marched to prison, transferred to Gijón, in Asturias, just before the fall of Santander and for a week or two were in grave danger of summary execution.

The details of his flight had been arranged in London by a certain Major Hugh Pollard, one of those romantic Englishmen who specialize in other countries’ revolutions.

The Nationalists started with the great advantage that the most important of the fighting Services, the Army, was on their side.

Their difficulty was that the crews, having murdered their officers, were unable to sail or fight the ships effectively until, later on, they were trained and officered by Russians.

So perished in the first few months of the war the finest flower of Spain.

Less wisely, they opened the prisons. These, as Señor de Madariaga points out,9 had been emptied months earlier of their political prisoners by an amnesty of President Azaña, and so could disgorge only common criminals. The latter were immediately enrolled in the various militias, and were responsible for much of the violence and horror that disgraced Republican Spain in the early months of the war.

Apart from Andalusia, where the Anarchist tradition was strong among the peasantry, it is reasonable to say that the agricultural districts were for the Nationalists, the cities and industrial areas were for the Republicans. Thus,

The Russians did for the Republicans roughly what the Germans did for the Nationalists—they supplied technicians and war material of all kinds. In return they exacted a far greater measure of control over Republican policy and strategy than the Germans were able to obtain from Franco; the price of Russian co-operation was Russian direction of the war and the complete domination by the Communist Party of all Republican political and military organizations.14

On many occasions during those early days it was the courage and initiative of individual commanders that turned the scale for the Nationalists. At the end of the war, when I was in Madrid, I heard the comment of an Englishman who had witnessed both the Russian and Spanish revolutions: ‘If Franco’s generals hadn’t had more guts than the White Russian generals, Spain would now be Communist.’

Their job was not made easy for them by the attitude of the military, which seemed to be that all foreign correspondents were spies who must be kept as far as possible from the scene of operations, who were only in the country on sufferance and who ought to be more than satisfied with whatever news the Army cared to issue in the official communiques. This was in marked contrast to the attitude of the Republicans, whose Press and Propaganda services were far superior to those of the Nationalists as their fighting was inferior and who took pains to give journalists and writers all the facilities they required. Although both sides imposed a rigid censorship on all dispatches going out of the country, the Nationalist made virtually no concessions to the Press, while the Republicans laid out enormous sums on propaganda abroad. These factors account in a large measure for the poor Press which the Nationalist received—and of which they ceaselessly complained—in England and the United States.

to look at the ruins of the Alcázar. There was nothing but a vast pile of rubble; the cellars, even the foundations, lay bare, with twisted iron girders sticking through the broken masonry and a great pit in the middle where the Republicans had exploded a mine. From the débris rose a foul stench of ordure and decay. The houses all around the square were pocketed with bullet holes, their windows shattered. A young Carlist from Galicia told us: ‘We are going to leave it like that as a monument to Marxist civilization.’ In fact, no attempt has been made to rebuild the Alcázar, and when I revisited it in the spring of 1951 it looked, and smelt, exactly the same.

It was early when we went to bed but late before I found my sleep. This was due partly to the thoughts racing through my mind, partly to the strangeness of my bed but chiefly to the thunderous sounds punctuating the stillness as my companions broke wind throughout the night.

The day after my arrival two troopers reported for duty incapably drunk; apparently they were old offenders. The following evening Llancia formed the whole Squadron in a hollow square in the main barrack-room. Calling out the two defaulters in front of us he shouted, ‘There has been enough drunkenness in this Squadron. I will have no more of it, as you are going to see.’ Thereupon he drove his fist into the face of one of them, knocking out most of his front teeth and sending him spinning across the room to crash through two ranks of men and collapse on the floor. Turning on the other he beat him across the face with a riding crop until the man dropped half senseless to the ground. He returned to his first victim, yanked him to his feet and laid open his face with the crop, disregarding his screams until he fell inert beside his companion. Then he turned to us: ‘You have seen, I will not tolerate a single drunkard in this Squadron.’ The two culprits were hauled, sobbing, to their feet to have half a bottle of castor oil forced down their throats. They were on duty next day, but I never saw either of them drunk again.

As we came over the crest San Merano gave the order, ‘Charge!’ Spurring our horses, we swept downhill in a cheering line, leaning forward on our horses’ necks, our sabres pointed. In a moment of mad exhilaration I fancied myself one of Subatai’s Tartars or Tamerlane’s bahadurs. Whoever, I exulted, said the days of cavalry were past? Preoccupied with these thoughts and with my efforts to keep station I never thought of looking at our target; nor, it seemed, did anyone else. For the next thing I knew we were in the middle of a bleating, panic-stricken, heard of goats, in the charge of three terrified herdsmen.

The enemy were evidently respecting the hour of the siesta for everything was quiet when we arrived. The

Father Vicente, in great spirits, dominated the gathering. He was the most fearless and the most bloodthirsty man I ever met in Spain; he would, I think, have made a better soldier than priest.

At first they made no progress against our fire. Many fell; some lay down where they were and fired back at us, others turned and ran in all directions, looking for cover, not realizing that this was the most certain way of being killed.

Parties with more divergent political views than the Requetés and the Falange could scarcely be imagined. Writing of ‘this magnificent Harlequin’, Señor de Madariaga says it was ‘as if the President of the United States organized the Republican-Democratic-Socialist-Communist-League-of-the-Daughters-of-the-American-Revolution, in the hopes of unifying American politics’. Either the Falange or the Requetés would have to dominate; the skill at intrigue of the former, and the political ineptitude of the latter made the outcome certain; the Requetés ceased to exert any serious influence on Spanish politics.

A former Chief of Police of the Irish Free State, General O’Duffy launched into Irish politics in the 1930’s, forming his own United Party, or ‘Blueshirts’. Seeing in the Spanish Civil War a chance to increase his prestige in Ireland, he raised a ‘Brigade’ of his countrymen to fight for the Nationalists. The ‘Brigade’ was in fact equal in strength to a battalion, but O’Duffy was granted the honorary rank of General in the Spanish Army.

Like some other Irishmen and some Americans—happily a minority—whose minds cherish the memory of past enmity he had a pathological hatred of the English, which he never tried to conceal. To his men he was known as ‘General O’Scruffy’ or ‘Old John Bollocks’.

It seems to me that nothing illustrates better the superiority of Republican propaganda over Nationalist than the Republican story about Guernica was given immediate and world-wide publicity, and is still generally believed; whereas the Nationalist case scarcely received a hearing.

At a smaller table nearby sat the newspaper correspondents, among them Randolph Churchill, Pembroke Stevens, Reynolds Packard and his wife and Philby of The Times; Churchill’s clear, vigorous voice could be heard deploring with well-turned phrase and varied vocabulary the inefficiency of the service, the quality of the food and, above all, the proximity of the Germans, at whom he would direct venomous glances throughout the meal. ‘Surely,’ he exclaimed loudly, ‘there must be one Jew in Germany with enough guts to shoot that bastard Hitler!’