-

On Vietnam, addiction, and substitutions

I saw the “During the Vietnam war American troops used lots of opiates , but when the troops came home very few of them continued using” line again.

I saw it on this substack post. Go ahead and read their entire post for more detail on their theories, but proponents of the this theory usually mention community and environment as inherent to the addiction process.

That could be the case, but one GIANT missing part of this story is that all of the troops went from a place where opiates, in the form of heroin, were common (Vietnam) to a place where alcohol was common (America). The human body substitutes opiates and alcohol easily. In and of itself a dropoff in opiate use proves nothing. The troops could just switch from heroin to the culturally celebrated and easily accessible alcohol. People use this example over and over without ever considering substitution.

-

Dogs in the parlor

-

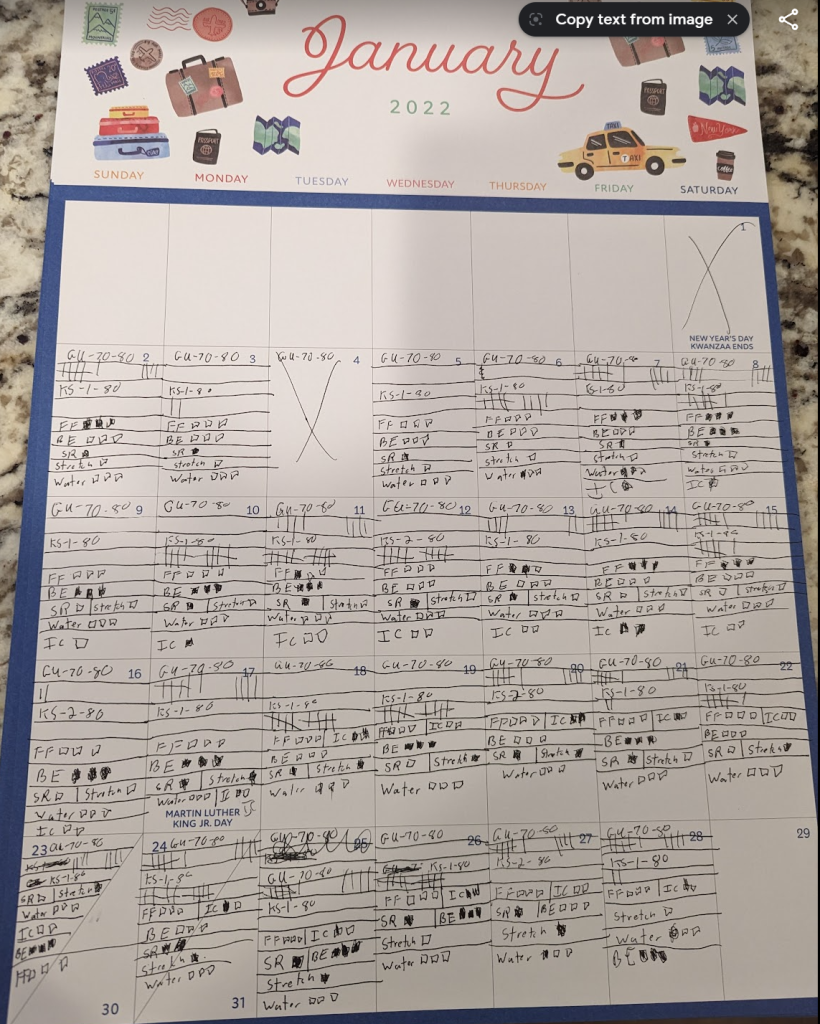

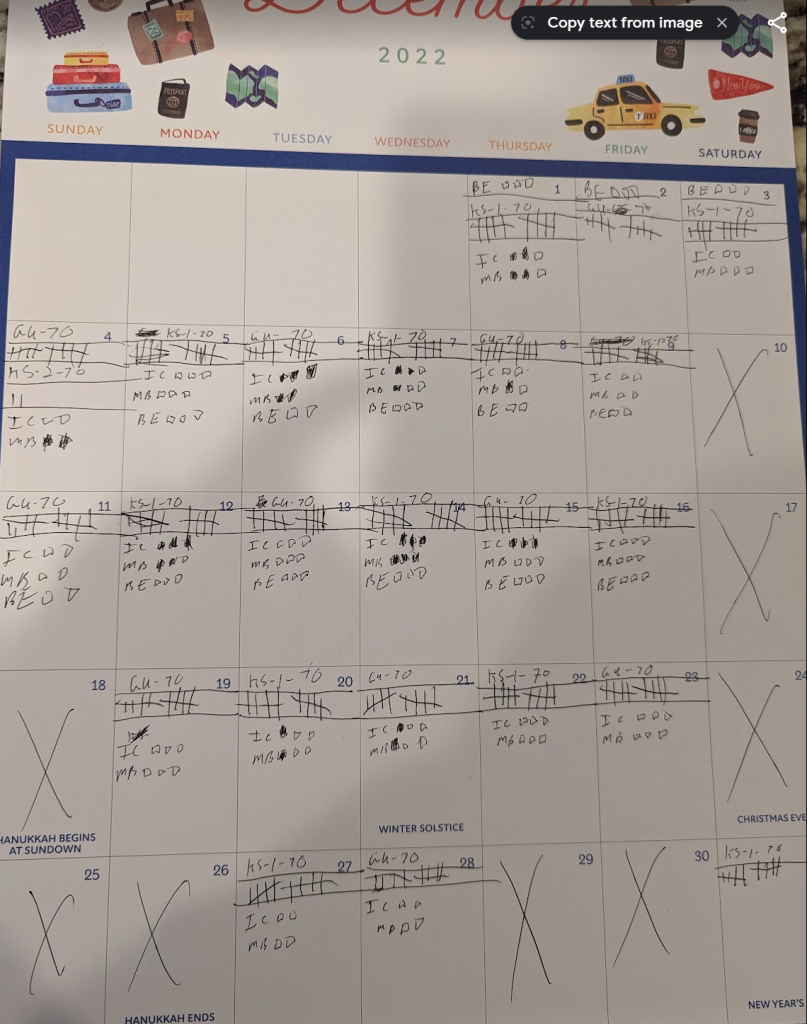

If it gets measured, it gets managed

And arguably improved – the January to December results show “limited” progress, but that does not show the real progress. I was advancing far too quickly and the lifts were getting to be feats of strength, and not refinements of technique, which is dangerous with kettlebells.

I went to a lower weight early in the year and have been moving back up with better technique ever since.

I’m going to wait until February before I introduce the 80 lb kettlebell back. I could probably do it now, but there is no need to rush. Also – my shoulders feel great, which was not the case this time last year.

-

Eric Hoffer: The Longshoreman Philosopher by Thomas Bethell

From my notion book review template

The Book in 3 Sentences

- This book is an honest account of the life of Eric Hoffer. It is an honest summary, including actual independent research and not just Hoffer’s version of his life. Bethell focuses his attention on his life and hot his political views.

Impressions

I liked it a lot – it did actual research and dispelled lots of the Eric Hoffer self created legend and made him a much more interesting and mysterious character. This is one of the rare cases where more details adds mystery instead of taking it away.

How I Discovered It

An Amazon recomendation

Who Should Read It?

Eric Hoffer Fans

How the Book Changed Me

How my life / behaviour / thoughts / ideas have changed as a result of reading the book.

I don’t think it will change anything – perhaps it increases my willingness to disbelieve weird life origin stories in favor of even weirder life origin stories.

My Top 6 Quotes

- Quite possibly, he was born in Germany and never became a legal resident of the United States.

- It seems extraordinary, then, that no one from Hoffer’s early life should ever have shown up. Possibly—just possibly—he actually came to America for the first time across the Mexican border in 1934, the year after the El Centro camp was opened. Perhaps he walked to San Diego and was by then every bit as hungry as he said he was, ate some cabbage “cow fashion,” and found the truck driver who took him to El Centro.

- It’s understandable that Hoffer might have concealed his background if he were indeed undocumented. If born abroad he was not an American citizen, for he never went through any naturalization ceremony. Congress severely restricted immigration to the United States in 1924 and by the 1930s, when jobs were scarce, U.S. residents found to be here illegally were deported without due process. Some were minor children born in the United States. In one report, “between 1929 and 1935 some 164,000 people were deported for being here illegally, about 20 percent of them Mexican.”32 Others estimate that between 1929 and 1939 as many as a million people were unceremoniously repatriated, many of them to Mexico. If Hoffer himself was in the United States illegally, he was wise to keep quiet about it.

- Hoffer’s blindness has functioned in all accounts as an alibi, explaining why he didn’t go to school, didn’t have friends, spoke with a German accent, had “shadowy” recollections, and so on. How reliable is his blindness story?

- Much later, Hoffer decided that “the social scientist is no more a scientist than a Christian scientist is a scientist.”

- An ideal environment for him, he said, was one in which he was surrounded by people and yet not part of them.

Summary + Notes

Highlights

As for Hoffer, Selden said: “All his conclusions are wrong—every one of them. But he writes beautifully and he asks the right questions.” They remained on good terms, and when Eric Hoffer died two years later, in the room where we had met, Selden was with him. His date of birth is uncertain, often given as 1902 but more likely 1898. And the account he often gave of losing his sight at an early age and then regaining it several years later doesn’t fit with some Quite possibly, he was born in Germany and never became a legal resident of the United States. Over the next thirty-three years she knew him better than anyone in the world. But, she said: “I never met anyone who knew Eric in his earlier life.” One day, when he was six, she fell down a flight of stairs while she was carrying him. Two years later, she died and Hoffer went blind. His blindness lasted for eight years. When asked, “Did the fall cause those things?” he responded, “I don’t know.”5 Hoffer also didn’t remember the fall itself, nor could he recall whether his sight returned suddenly or gradually. In an early account he said that he went “practically blind,” followed by a “gradual improvement.” Martha Bauer was a “Bavarian peasant” and his German accent came from It seems extraordinary, then, that no one from Hoffer’s early life should ever have shown up. Possibly—just possibly—he actually came to America for the first time across the Mexican border in 1934, the year after the El Centro camp was opened. Perhaps he walked to San Diego and was by then every bit as hungry as he said he was, ate some cabbage “cow fashion,” and found the truck driver who took him to El Centro. and during those fifteen years Cole saw Hoffer almost every week. His account coincides with Lili’s: “I never met a single person who knew him before he worked on the waterfront.” It’s understandable that Hoffer might have concealed his background if he were indeed undocumented. If born abroad he was not an American citizen, for he never went through any naturalization ceremony. Congress severely restricted immigration to the United States in 1924 and by the 1930s, when jobs were scarce, U.S. residents found to be here illegally were deported without due process. Some were minor children born in the United States. In one report, “between 1929 and 1935 some 164,000 people were deported for being here illegally, about 20 percent of them Mexican.”32 Others estimate that between 1929 and 1939 as many as a million people were unceremoniously repatriated, many of them to Mexico. If Hoffer himself was in the United States illegally, he was wise to keep quiet about it. Hoffer also spoke German and did so fluently. Hoffer’s blindness has functioned in all accounts as an alibi, explaining why he didn’t go to school, didn’t have friends, spoke with a German accent, had “shadowy” recollections, and so on. How reliable is his blindness story? There is no Martha, and in this account he clearly lived with this aunt for a year after his father died, thus accounting for the gap between his father’s 1920 death and his 1922 departure for Los Angeles. Hoffer’s later and oft-repeated account of a $300 legacy from his father’s guild is also contradicted. “Martha had often consoled him with the advice: ‘Don’t worry Eric. You come from a short-lived family. You will die before you are forty. Your troubles will not last long.’ ” These thoughts All attempts to locate Hoffer or his parents, Knut and Elsa, in the Bronx, either through census data or Ancestry.com, have drawn a blank. He was almost forty years old before he acquired a definite street address. What may be more likely is that Hoffer came to America as a teenager or young adult and never did live in New York. It’s easy to understand why Hoffer would make up an American background if he was eager to avoid questions about his citizenship, but why so elaborate a ruse? Hoffer was a great storyteller, and he insisted that a writer should entertain as well as inform his audience. He was also a master at diverting attention from his own background. Finally, he did provide a few hints that his story shouldn’t be taken too seriously. Much later, Hoffer decided that “the social scientist is no more a scientist than a Christian scientist is a scientist.” But Although they were white Anglo-Americans, Starr writes, and often fleeing from the Dustbowl in Oklahoma, Texas, and elsewhere, they were regarded as a despised racial minority by much of white California. In 1935 California had 4.7 percent of the nation’s population but triple that percentage of its dependent transients. worked.” He described Hoffer as a natural loner; in fact, all his life he wanted to be left alone. For many years his relations with women were therefore confined, with one exception, to prostitutes.19 Koerner adds that Hoffer was “terrifically lusty”: The earliest documentary record of Hoffer’s existence is a photostat of his application for a Social Security account, filled out on June 10, 1937. He said at the time that he was thirty-eight years old, having been born in New York City on July 25, 1898. If so, of course, he was four years older than he claimed at other times. identified himself as the son of Knut Hoffer and Elsa Goebel, and gave his address as 101 Eye Street, Sacramento. His employer at the time was the U.S. Forest Service in Placerville, California. It is the only documentary evidence of his life to be found in the archives before he moved permanently to San Francisco. Vigorous walking seems to ease the flow of words; and The feeling of being a stranger in this world is probably the result of some organic disorder. It is strongest in me when I’m hungry or tired. But even when nothing is wrong I sometimes find it easy to look at the world around me as if I saw it for the first time. The war, the nationwide draft, and a labor shortage on the docks made it possible for him to become a longshoreman at the age of forty-five. There were many accidents. In 1943 a five-ton crate crashed to the wharf and just missed him, but it destroyed his right thumb. He was in the hospital for months as a new one was reconstructed from his own thigh. It was little more than a stump. my case conditions seem ideal. I average about 40 hours a week, which is more than enough to live on. And all I have to do is put in 20 hours of actual work. It’s a racket and I love it. Selden became a “diet faddist,” and Hoffer noticed that, too. How true is it, he wondered, “that true believers have an affinity for diet cults? You attain immortality either by embracing an eternal cause or by living forever.” Selden told Eric that when he ate, he methodically chewed so many times on one side, so many times on the other. “It would be hard to find another occupation with so suitable a combination of freedom, exercise, leisure and income,” he wrote to Margaret Anderson in 1949. “By working only Saturday and Sunday (eighteen hours at pay and a half) I can earn 40–50 dollars a week. This to me is rolling in dough.”10 But in a 1944 notebook he recorded that creative thought was incompatible with hard physical work. An ideal environment for him, he said, was one in which he was surrounded by people and yet not part of them. But routine work was compatible with an active mind. On the other hand a highly eventful life could be mentally exhausting and drain all creative energy. He cited John Milton, who wrote political pamphlets throughout the Puritan agitation, and postponed Paradise Lost until his life was more peaceful. Clumsiness, he concluded, is inconspicuous for those who are not on their home turf. Similarly, the cultural avant-garde attracts people without real talent, “whether as writers or artists.” Why? Because everybody expects innovators to be clumsy. “They are probably people without real talent,” he decided. But those who experiment with a new form have a built-in excuse.11 and it began with this issue. The union “was run by nobodies,” just like America, Hoffer said. “It did not occur to the intellectuals,” Hoffer commented, “that in this country nobodies perform tasks which in other countries are reserved for elites.” It was one of his favorite reflections. Financial records show that Hoffer made $4,100 as a longshoreman and $1,095 in True Believer royalties in 1953. The examples of Lenin, Mussolini and Hitler, where intellectually undistinguished men made themselves through faith and single-minded dedication into shapers of history is a challenge to every mediocrity hungering for power and capable of self delusion. During the day it occurred to me that if it were true that all my life I have had but a single train of thought then it must be the problem of the uniqueness of man. Most days he set off for a “five mile hike in the Golden Gate Park,” he wrote, and there he found that he could “think according to schedule”: I have done it every day for weeks. Each day I took a problem to the park and returned with a more or less satisfactory solution . . . The book was written in complete intellectual isolation. I have not discussed one idea with any human being, and have not mentioned the book to anyone but A visiting reporter, Sheila K. Johnson of the Los Angeles Times, said of this apartment: “There are no pictures on the walls, no easy chair, no floor lamps, no television set, no radio, no phonograph. There are in short no distractions.” Hoffer himself received his retirement papers from the longshoremen’s union in 1966. He may have already received that news when he accompanied Tomkins to the docks later that Here is a case where a genuine belief in God would make a difference. He is obviously drifting to an unmarked grave in a godforsaken graveyard. In lucid intervals he drifts back to San Francisco but does not stay long.2 “He wanted to change the world, and he wanted to change it alone,” Lili recalled. “He made a single convert—his mother.” Years after his death, reflecting on her former husband’s impractical nature, Lili still seemed amazed. “The idea that he chose to express his ideas was by leaflets,” she said with an emphasis that conveyed her frustration. Reflecting on Hoffer’s account of his early life, and the implausibility of his claim that as a large child he was carried downstairs by a small woman who tumbled and then died, Gladstone said: “I don’t believe a word of it.” In 1979, Eric moved to Alaska, became a fisherman, married, and had a family. He lives in western Alaska to this day. At the San Francisco reception following his mother’s funeral in October 2010, Eric (by now the father of six) was receptive to the idea that Hoffer’s account of his early life didn’t quite add up. He thought Hoffer’s case might be comparable to that of B. Traven, the mysterious German author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. (B. Traven was a pen name for a German novelist whose actual identity, nationality, and date and place of birth are still unknown. The book, published in Germany in 1927, then in English in 1935, was made into the famous movie of the same name in 1948.) Of the paternity question, Stephen said, “Has there been a DNA test? No. But Eric suspected that Hoffer [which he pronounced Hoafer] was his father. He asked my mother and she said yes.” I have been generous with myself and my money and the truth is that Selden did not love Lili and felt my invasion as a liberation. He told me yesterday that my intrusion enriched the children’s life and whatever I have saved will be theirs when I am gone. My attachment to Lili after 33 years is undiminished. In Lili’s hand beneath she wrote: “Dear, dear Eric! Always beloved.” Some of these fanatics act out of the weakness of their personalities, the reviewer added; some out of the strength. But by the end of the book Hoffer had brought “the fanatical leader and the fanatical follower into a single natural species.” True believers don’t start mass movements, Hoffer wrote. That is achieved by “men of words.” But the true believers do energize those movements. Hoffer’s understanding of the relationship between true believers and mass movements was Hitler’s relationship to the Nazi Party. The German Workers Party—its name was later changed—was founded in 1919. Hitler soon joined it and ousted the founder, Anton Drexler, in 1921. With all the zeal of the true believer, Hitler infused it with fanaticism and Nazism became a mass movement. Hoffer did not make this Hitler relationship explicit in his book but it was his unstated guide. “the preoccupation with the book is with theories—right or wrong. I cannot get excited about anything unless I have a theory about For a movement to prevail, the existing order must first be discredited. And that “is the deliberate work of men of words with a grievance.” If they lack a grievance, the prevailing dispensation may persist indefinitely.8 Sometimes, a regime in power may survive by co-opting the intellectuals. The partnership between the Roman rulers and the Greek men of words allowed the Roman Empire to last for as long as it did. As Hoffer saw it, then, men of words laid the groundwork for mass movements by creating receptivity to a new faith. This could be done only by men who were first and foremost talkers or writers, recognized as such by all. If that ground had not been prepared, the masses wouldn’t listen. True believers could move in and take charge only after the prevailing order had been discredited and had lost the allegiance of the masses.11 Mass movements are not equally good or bad, Hoffer wrote. “The tomato and the nightshade are of the same family, the Solanaceae,” and have many traits in common. But one is nutritious and the other poisonous.12 In adding this he was probably responding to another caution from Fischer, who wrote that some in-house readers “. . . got the impression that Hoffer is implying that all mass movements are equally good or bad, that the ideas on which they are based are always predominantly irrational, and that from the standpoint of value judgments there is not much distinction between, say, the Nazi movement, Christianity, and the Gandhi movement in India.” The Harper contract to publish the book was sent to Hoffer in June 1950. Harper scheduled the book for publication and, not surprisingly, wanted some independent report about this mysterious author who was unreachable by phone, worked on the docks, had never gone to school, and yet wrote so well. After publication, some reviewers, including the New York Times’s Orville Prescott, also called the work cynical—“as cynical about human motives as Machiavelli.”14 The libertarian author Murray Rothbard, writing for Faith and Freedom under the pen name Jonathan Randolph, was also highly critical. “Hoffer may be anti-Communist,” he wrote, “but only because he sneers at all moral and political principles.” Hoffer later became openly political, attacking Stalin, Communism, and leftist intellectuals en masse. He had “a savage heart,” he reflected, and “could have been a true believer myself.”17 America and Israel were to become his great causes. But the neutrality of The True Believer contributed to its critical success. Fischer also pointed out that the book would be more readable “if the author would make greater use of examples and illustrations.” Readers of The True Believer do indeed encounter a sea of abstractions—fanaticism, enthusiasm, substitution, conversion, frustration, unification—and many will have scanned its pages, often in vain, looking for the tall masts and capital letters of a proper name. As a historical assessment, nonetheless, Hoffer’s treatment was questionable on several fronts. Longevity was just one. Nazism lasted for twelve years, Communism’s span was measured in decades, while Christianity has endured for two thousand years and shows no sign of disappearing. Pipes has great admiration for Hoffer and assigned The True Believer to his Harvard class. “Mass movements do occasionally occur,” he added, “but my feeling is that most such movements are organized and directed by minorities simply because the ‘masses,’ especially in agrarian societies, have to get back to work to milk the cows and mow the hay. They don’t make revolutions: they make a living.” Communism resembled a religion but it was the faith of disaffected Western intellectuals, not of the masses. After the immediate revolutionary fervor cooled it was sustained, in Russia and everywhere else, by coercion and terror. Communism never did bring about a release of human energies—or if so, only for a short time. The explosive component in the contemporary scene, Hoffer wrote, was not “the clamor of the masses but the self righteous claims of a multitude of graduates from schools and universities.” An “army of scribes” was working to achieve a society “in which planning, regulation and supervision are paramount, and the prerogative of the educated.” In its May 22, 1983, obituary on Hoffer, the Washington Post said that The True Believer is “difficult to summarize [but] easy to admire.” In contemplating the mystery of Eric Hoffer, Lili Osborne would ask herself how a self-educated laborer came to write so abstract a work. His early manuscripts had shown that he was a polished writer before he (apparently) had much experience of writing anything. His comments to Margaret Anderson give one or two clues. Looking back over his earlier notebooks, he was surprised to find how hard it had been for him to reach insights “which now seem to me trite.” The key was that “the inspiration that counts is the one that comes from uninterrupted application.” Sitting around waiting for lightning to strike got one nowhere. His rewritten drafts of The True Believer showed how much he owed to perseverance. His self-assurance and stylistic mastery were remarkable coming from someone who had not yet published anything. But if his success with The True Believer were to be attributed to any single quality, it would be his capacity to concentrate and persevere. His ability to exercise these talents also explained his self-confidence. Still, the mystery never quite goes away. warning them that woe betides a society that reaches a turning point and does not turn. He worried that if workers’ skills were no longer needed they might become “a dangerously volatile element in a totally new kind of American society.” America itself might be undermined—no longer shaped by “the masses” but by the intellectuals. Hoffer increasingly saw them emerging as villains in the continuing American drama. The culmination of the industrial revolution should enable the mass of people to recapture the rhythm, the fullness and the variety of pre-industrial times. By now Hoffer’s life story was fixed. The KQED version became, in effect, the canonical account. In later interviews—by Tomkins, James Koerner, Eric Sevareid, and others—Hoffer stuck to the same script, sometimes almost word for word. He told the same anecdotes with no new details. The inconsistencies in his earlier accounts were gone. It was as though by 1963 he had settled on the story of his life and he no longer deviated from it. Later, the FBI heard that Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, an assistant professor at Berkeley at that time, might have visited the class; at one point, agents combed through Hoffer’s papers at Hoover. “Anyone could drop in to Hoffer’s class,” Cole said. “But they never established that Ted Kaczynski was there. Lili asked me if I remembered him. I didn’t.” So he taught himself Hebrew, “and his pronunciation was wonderful.” Cole heard Hoffer “more than a few times say something in Hebrew. He had such a great ear.” Hoffer told another interviewer that he had learned Hebrew while on skid row in Los Angeles. “I think I mastered it. I can speak it, but I cannot make out the text,” he said. He memorialized this appeal to brevity by funding the Lili Fabilli and Eric Hoffer Essay Prize at UC–Berkeley. It is awarded each year for the best essays of 500 words or less on a topic chosen by the Committee on Prizes. At least one of these columns was read by Pauline Phillips, the author of the “Dear Abby” column, who had been friends with Hoffer for some time. At the time of the anti-Soviet revolt in East Germany in 1953, Hoffer recognized the Communist evil. He noticed, too, that the West held Communism in awe.9 But he was also impressed by what Communism had apparently achieved. Stalin had shown unbounded contempt for human beings, but he could justify it by pointing to “the breathtaking results of sheer coercion.” Cruelty worked, in other words. “Idealism, courage, tremendous achievements both cultural and material, faith and loyalty unto death can be achieved by relentless, persistent coercion.” That industrial production had in fact collapsed following the Bolshevik Revolution and had made only a faltering recovery was not appreciated for decades. Led by U.S. government agencies that took Soviet statistics at face value, policy analysts and economic textbooks continued making the same mistake right up to 1989. As always, he was aiming for the widest generalization. An enduring problem was that Hoffer was not interested in economics and paid little attention to political institutions. He either took private property and the rule of law for granted, or thought them unimportant. “Far more important than the structure of a governmental system is the make-up of the men who operate it,” he wrote in 1952. He persisted, surely, because his underlying argument—mass movements had animated societies by releasing pent-up energies—came from The True Believer.13 Abandon this search, then, and his argument about the role of mass movements might collapse. He had referred to his new book as “vol. 2.” His prolonged difficulty with that unwritten book was rooted in “vol. 1,” on which his reputation was largely based. Later on, Hoffer was inclined to ignore and even to disparage mass movements. He had no wife and no debts, and his rent was as low as rents in San Francisco ever get. His expenses were minimal and his frugality ingrained. Pen, paper, and books from the public library were for him the key ingredients of contentment. When A related theme was often found in his notebooks: “What tires us most is work left undone.” He kept insisting that he was not a writer, but to continue functioning he had to keep on writing: He also saw reasons for believing that “Russia’s day of judgment will come sometime in the 1990s.” (The Soviet Union was always “Russia” in Hoffer’s lexicon.) “And when the day comes everyone will wonder that few people foresaw the inevitability of the end.” There will be no peace in this land for decades. The journalists have had a taste of history-making and have become man-eating tigers. Life will become a succession of crises . . . What will political life be like when history is made by journalists? As a symptom of aging, he noted what many in retirement have reported: he felt hurried though no one was pursuing him. Working on an essay about the old, he knew that “to function well the old need praise, deference, special treatment—even when they have not done anything to deserve it. Old age is not a rumor.” They say that on his deathbed Voltaire, asked to renounce the devil, said: “This is no time to be making new enemies.” This talk of living a life of quiet desperation is the blown-up twaddle of juveniles and if it hits the mark it does so with empty people. I have no daemon in me; never had. There is a murderous savagery against people I have never met; a potential malice which is not realized because of a lack of social intercourse. In the usual sense of the word, Hoffer himself was an intellectual. He read books and wrote them. But he had no desire to teach others, he said, and this made him “a non-intellectual.” For the intellectual is someone who “considers it his God-given right to tell others what to Another correspondent was the community organizer Saul Alinsky. the language is cryptic because the idea is not clear.” He viewed them as a dangerous species. They scorn profit and worship power; they aim to make history, not money. Their abiding dissatisfaction is with “things as they are.” They want to rule by coercion and yet retain our admiration. They see in the common criminal “a fellow militant in the effort to destroy the existing system.” Societies where the common people are relatively prosperous displease them because intellectuals know that their leadership will be rejected in the absence of a widespread grievance. The cockiness and independence of common folk offend their aristocratic outlook. The free-market system renders their leadership superfluous. Their quest for influence and status is always uppermost. free society is as much a threat to the intellectual’s sense of worth as an automated economy is a threat to the worker’s sense of worth. Any social order, however just and noble, which can function well with a minimum of leadership, will be anathema to the intellectual. The intellectual regards the masses much as a colonial official views the natives. Hoffer thought it plausible that the British Empire, by exporting many of its intellectuals, had played a counter-revolutionary role at home. Employment and status abroad for a large portion of the educated class may have “served as a preventive of revolution.” All intellectuals are homesick for the Middle Ages, Hoffer wrote. It was “the El Dorado of the clerks”—a time when “the masses knew their place and did not trespass from their low estate.” Eric Osborne recalled one humorous incident: “Once Eric Hoffer was talking and a rabbi was in the audience; or maybe Hoffer was talking to a bunch of rabbis, and he was telling them that there is no God. One rabbi said, ‘Mr. Hoffer, there is no God and you are His prophet.’ Yet he continued to ponder the nature of God. It was speculation without faith—more philosophy than religion—but it was never far from his mind. In his notebooks he often wrote as though God was a reality whether he believed in Him or not. And he did (sometimes) capitalize the pronoun. Sometimes you think how much of a better world it would be if Judaism, Christianity and Islam with their driving vehemence had never happened. Then you think of all the misery and boundless cruelty practiced in lands that never heard of Jehovah, his son and his messenger. Hoffer’s ideas about the uniqueness of man and the great error of trying to assimilate man into nature—a key dogma of modernity—was perhaps his most original venture into philosophy. Hoffer was strongly opposed to the modern tendency to see science and religion as antagonists. On the contrary, religious ideas about the Creator had inspired the early scientists. They tried to work out how God had created the world and science emerged from this study. He believed Israel revealed that history is not a mere process, but an unfolding drama. The insights and thoughts that survive and endure are those that can be put into everyday words. They are like the enduring seed—compact, plain looking and made for endurance. La Rochefoucauld, in his maxims, delighted Hoffer with his brevity and wit, sometimes bordering on cynicism (“We are always strong enough to bear the misfortunes of others”). Philosophers, on the other hand, had little to boast about. Why was this? Russell concluded, “As soon as definite knowledge concerning any subject becomes possible this subject ceases to be called philosophy and becomes a separate science. The whole study of the heavens, which now belongs to astronomy, was once included in philosophy; Newton’s great work was called ‘The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy.’ Similarly, the study of the human mind, which was a part of philosophy, has now become separated from philosophy and has become the science of psychology. . . . [Only those questions] to which, at present, no definite answer can be given, remain to form the residue which is called philosophy.”1 He once wrote that “the trouble with the Germans is that they are trying to express in prose what could only be expressed in music.” There was “a German desire for murkiness,” Hoffer argued, “a fear of the lucid and tangible.” Worse, “the German disease of making things difficult” had conquered the world. The less we know of motives, the better we are off. Worse than having unseemly motives is the conviction that our motives are all good. The proclamation of a noble motive can be an alibi for doing things that are not noble. Other people are much better judges of our motives than we are ourselves. And their judgment, however malicious, is probably correct. I would rather be judged by my deeds than by my motives. It is indecent to read other people’s minds. As for reading our own minds, its only worthwhile purpose is to fill us with humility. Nowhere is freedom more cherished than in a non-free society, for example. “An affluent free society invents imaginary grievances and decries plenty as a pig heaven.” As for deciphering others, the only real key is our self. And considering how obscure that is, “the use of it as a key in deciphering others is like using hieroglyphs to decipher hieroglyphs.” Sophistication is for juveniles and the birds. For the essence of naivety is to see the familiar as if it were new and maybe also the capacity to recognize the familiar in the unprecedentedly new. There can be no genuine acceptance of the brotherhood of men without naivety. The most intense insecurity comes from standing alone. We are not alone when we imitate. So, too, when we follow a trail blazed by others, even a deer trail. At times he felt euphoric and he wondered how that arose. He came to believe that “the uninterrupted performance of some tasks” was the key to happiness. It was not the quality of the task, which could be trivial or even futile. “What counts is the completion of the circuit—the uninterrupted flow between conception and completion. Each such completion generates a sense of fulfillment.” Whenever conditions are so favorable that struggle becomes meaningless man goes to the dogs. All through the ages there were wise men who had an inkling of this disconcerting truth. . . . There is apparently no correspondence between what man wants and what is good for him. Flaubert and Nietzsche have emphasized the importance of standing up and walking in the process of thinking. The peripatetics were perhaps motivated by the same awareness. Yet purposeful walking—what we call marching—is an enemy of thought and is used as a powerful instrument for the suppression of independent thought and the inculcation of unquestioned obedience. Originality is not something continuous but something intermittent—a flash of the briefest duration. One must have the time and be watchful (be attuned) to catch the flash and fix it. One must know how to preserve these scant flakes of gold sluiced out of the sand and rocks of everyday life. Originality does not come nugget-size. Like Hoffer, Montaigne almost never mentioned his mother, who came from a family of Sephardic Jews. Hoffer said that when he read Montaigne’s essays in 1936 he felt “all the time that he was writing about me. I recognize myself on every page.” Overall, however, he found it remarkable “how little we worry about the things that are sure to happen to us, like old age and death, and how quick we are to worry ourselves sick about things which never come to pass.” Montaigne said something very similar. His life had been full of “terrible misfortunes,” he said, “most of which never happened.” Theorizing in the future, he predicted, would tend to regard humanity “as unchangeable and unreformable.” “I shall not welcome death,” Hoffer wrote. “But the passage to nothingness seems neither strange nor frightful. I shall be joining an endless and most ancient caravan. Death would be a weary thing had I believed in heaven and life beyond.” September 27, 1981 How does a man die? Does he know when death approaches? Friday night (25th) I vomited the first time in my life. The vomit was dark and bitter. The new experience of vomiting gave me the feeling that I was entering the realm of the unknown. As they lay there in the dark, Selden once again heard Eric’s heavy breathing. Reassured, Selden went back to sleep. But when he woke up again, perhaps an hour or two hours later, Eric’s breathing could be heard no more. He was gone—you could say that he didn’t say goodbye to anyone. He was buried at the Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma, just outside San Francisco. Lili Osborne’s grave is next to his. the well-off will no longer be able to derive a sense of uniqueness from riches. In an affluent society the rich and their children become radicalized. They decry the value of a materialist society and clamor for change. They will occupy positions of power in the universities, the media, and public life. In some affluent societies the children of the rich will savor power by forming bands of terrorists. Bacon touches upon two crucial differences between Judeo-Christianity and other religions. In a monotheistic universe nature is stripped of divine qualities—this is a downgrading of nature. At the same time, in a monotheistic universe, man is wholly unique, unlike any living thing. It would have gone against Bacon’s aristocratic grain to point out that the monotheistic God, unlike the God of other religions, is not an aristocrat but a worker, a skilled engineer. Bacon could have predicted the coming of a machine age by suggesting that if God made man in his own image, he made him in the image of a machine-making engineer. An aphorism states a half truth and hints at a larger truth. To an aphorist all facts are perishable. His aim is to entertain and stimulate. Instruction means the stuffing of people with perishable facts. And since in human affairs the truthful is usually paradoxical, aphoristic writing is likely to prove helpful. The French Revolution and its Napoleonic aftermath were the first instances of history on a large scale made by nobodies. The intellectuals loathe democracy because democracy creates a political climate without deference and worship. In a democracy the intellectual is without an unquestioned sense of superiority and a sense of social usefulness. He is not listened to and not taken seriously. The sheer possession of power does not satisfy the intellectual. He wants to be worshipped. years of pauseless killing of the First World War. This tangibility of death created a climate inhospitable to illusion.. But it is probably true that from the beginning of time talents have been wasted on an enormous scale. It is the duty of a society to create a milieu optimal for the realization of talents. Such a society will preach self-development as a duty—a holy duty to finish God’s work. Where the creative live together they live the lives of witches. -

The Story of Russia by Orlando Figes is one of the greatest history books I’ve ever read

TLDR – five stars, one of the best history books I’ve ever read. Go read it.

The Story of Russia by Orlando Figes is the history of Russia I’ve been looking for all these years. Figes’ writing is very good prose, concise, very well sourced and actually answers the questions like “how is it possible that {XXX} happened” to a greater degree than any book I’ve come across.

It starts at the very beginning where what we now call Russia formed (coalesced might be a better word) Unlike most histories of Russia it’s not just a listing of Czars and their internal political dramas but covers a lot of other life in Russia, i.e. peasants, workers, etc.

Figes makes the point again and again (the emphasis is correct) that there is, and has never been, that while family life is very strong, and the central government is strong, everything in between is weak. There are not, and have never been strong unions, minority political parties, non orthodox churches, non-state affiliated business, etc, etc. There were not any strong nobles, or regional powers. Essentially there is no middleware, which renders what we in the West think of as democracy impossible.

I think in every other country the monarch bubbled out of the nobility, in Russia it was the reverse.

One thing Figes did not highlight is how Russia land policies encouraged population growth in the pre-revolutionary times, in sort of a way that the pre-civil war American south favored the accumulation of slaves. “Human capital” became a very literal term. In the American south, the limiting factors were land and slaves to work the land. In Russia land was reallocated periodically according to the number of “eaters” which encouraged extremely high population growth, apparently higher than anywhere else. This meant very, very, weak property rights and consequently limited physical capital accumulation.

It seems that a lot of Russia has always lived under some form of village level proto-communism. It would be approximately Socialism 3.5 by this definition, but at the peasant village level.

I feel like reading it again just to let everything sink in. Figes wrote the most information dense book I’ve read in years.

Addendum – I now get much more of the Russian rhetoric regarding Ukraine, as well as references to “The Russias” instead of just Russia – the Anglosphere is sort of a comparison.

Things I highlighted in the book.

The only written account that we have , the Tale of Bygone Years , known as the Primary Chronicle , was compiled by the monk Nestor and other monks in Kiev during the 1110s .

in 862 , the warring Slavic tribes of north – west Russia agreed jointly to invite the Rus , a branch of the Vikings , to rule over them : ‘ Our land is vast and abundant , but there is no order in it . Come and reign as princes and have authority over us ! ‘

The timescale of the chronicle is biblical . It charts the history of the Rus from Noah in the Book of Genesis , claiming them to be the descendants of his son Japheth , so that Kievan Rus is understood to have been created as part of the divine plan . 4

Russia grew on the forest lands and steppes between Europe and Asia . There are no natural boundaries , neither seas nor mountain ranges , to define its territory , which throughout its history has been colonised by peoples from both continents . The Ural mountains , said to be the frontier dividing ‘ European Russia ‘ from Siberia , offered no protection to the Russian settlers against the nomadic tribes from the Asiatic steppe . They are a series of high ranges broken up by broad passes . In many places they are more like hills . It is significant that the word in Russian for a ‘ hill ‘ or ‘ mountain ‘ is the same ( gora ) . This is a country on one horizontal plain .

Pine forests give way to mixed woodlands and open wooded steppelands to the south of Moscow , where the rich black soil is in places up to several metres deep .

As their power grew , the Rus warriors attacked the Khazar tribute – paying lands between the Volga and Dnieper . In 882 they captured Kiev , which became the capital of Kievan Rus .

To grow the population and tax base of the new state the grand prince Vladimir forcibly transported entire Slav communities from the northern forests to the regions around Kiev . It was the start of a long tradition of mass population movements enforced by the Russian state .

Instead of the act of self – determination celebrated by the modern Russian and Ukrainian states , Vladimir’s conversion to the Eastern Church may have been a declaration of his kingdom’s subjugation to the Byzantine Empire .

Later it would be replaced by a high wall of icons , the iconostasis , whose visual beauty is a central feature of the Eastern Church . Seeing is believing for the Orthodox . Russians pray with their eyes open – their gaze fixed on an icon , which serves as a window on the divine sphere . 22 The icon is the focal point of the believers ‘ spiritual emotions – a sacred object able to elicit miracles . Icons weep and produce myrrh . They are lost and reappear , intervening in events to steer them on a divine path .

Of the 800 Russian saints created up until the eighteenth century , over a hundred had been princes or princesses . 26 No other country in the world has made so many saints from its rulers . Nowhere else has power been so sacralised .

At the core of the Russian faith is a distinctive stress on motherhood which never really took root in the Latin West . Where the Catholic tradition placed its emphasis on the Madonna’s purity , the Russian emphasised her divine motherhood ( bogoroditsa ) . This

Each prince was equipped with an army or druzhina of a few thousand horsemen led by warriors , known as boyars , who received part of the prince’s land .

On the death of the grand prince or one of his sons there was a reshuffling of the principalities held by the remaining kin . Normally the throne of the grand prince would pass , not from father to son , but from the elder brother to the younger one ( usually until the fourth brother ) . Only then would it pass down to the next generation . When the eldest brother took the throne in Kiev , all the others moved up to the principality on the next step of the ladder . It was a system of collateral succession not found elsewhere in Europe .

Kinship not kingship was its constitutional principle . The grand prince was not the equal of a king , but primus inter pares , a figurehead of unity . Outside Kiev itself , in the principalities , his authority was limited .

Kiev had a population of 40,000 people , more than London and not much less than Paris , at the start of the thirteenth century .

In fact , politically , Muscovy was different from Kievan Rus . Two hundred and fifty years of Mongol occupation had created a fundamental break between the two .

army was in a good position to conquer Europe , whose disunited countries had little chance of withstanding the onslaught . But the West was saved by the death of the great khan Ögedei , the favourite son of Chingiz Khan , in December 1241 . When Batu received the news , the following spring , he called off the western offensive and took his army back to Karakorum , the empire’s capital on the Mongolian steppe , to stake his claim to the succession .

They preferred indeed to fight in the winter when the rivers and marshlands – the main impediment to their horses – were frozen .

being punished by the Tatar infidels for its sins ( they called them the ‘ Tartars ‘ , with an extra ‘ r ‘ , to associate them with Tartarus , the Greek name for ‘ hell ‘ ) . In

So many craftsmen were captured by the Mongols that practically no stone or brick buildings were built in the half – abandoned towns during the next fifty years .

Nevsky’s collaboration was no doubt motivated by his mistrust of the West , which he regarded as a greater threat to Orthodox Russia than the Golden Horde , generally tolerant of religions . He

The Church too collaborated with the Golden Horde . The khan exempted it from taxation , protected its property and outlawed the persecution of all Christians , on condition that its priests said prayers for him , meaning that they upheld his authority . These dispensations allowed the Church to thrive . Under the Mongols it made its first real inroads into the pagan countryside .

An important part of this monastic movement was led by men of deep religious feeling who rebelled against the worldly hierarchies of the Orthodox Church and went into the wilderness to live an ascetic life of private prayer and contemplation , book – learning and manual work . They took their spiritual guidance from the hesychasm of Byzantium , a contemplative mysticism ( from the Greek hesychia , meaning ‘ quietude ‘ ) founded on the idea that the way to God was through a life of poverty and prayer under the guidance of a holy man or elder . The

the bringer of Christianity to the Komi people , who fought hard to defend their animist beliefs ( the artist Kandinsky found them still in existence when he visited the remote Komi region in 1889 ) ,

West . These lands ‘ political development was later shaped by the Polish – Lithuanian Commonwealth , a constitutional monarchy with an elected king and parliament dominated by the local landed nobles , which would rule this polyethnic area from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century .

The Mongols ‘ growing fear of Lithuania was also an important factor in their promotion of Moscow . In the early fourteenth century the Lithuanians were steadily expanding their control to the former western lands of Kievan Rus . Where they were unable to annex them by pressure or persuasion , the Lithuanians turned to religion . They established a separate metropolitan to prise away the western territories from the rest of Orthodox Russia . By the 1330s , Smolensk , Novgorod and Tver were all close to throwing in their lot with Lithuania ; Moscow was struggling to rein them in through military threats ; and the Mongols were confronted by the danger of a powerful new state appearing on their western frontier that might undermine their empire in the Russian lands .

‘ national awakening ‘ . Kulikovo is still celebrated in Russia . Putin has frequently referred to it as evidence that Russia was already a great power – the saviour of Europe from the Mongol threat – in the fourteenth century . This idea – Russia as a guard protecting Europe from the ‘ Asiatic hordes ‘ – became part of the national myth from the sixteenth century , as Muscovy began to see itself as a European power on the Asian steppe .

Today the Kulikovo victory is linked in the nationalist consciousness to other episodes when Russia’s military sacrifice ‘ saved ‘ the West , in 1812 – 15 ( against Napoleon ) or 1941 – 5 , for example ; each time its sacrifice had been unthanked , unrecognised by its Western allies in these wars . The country’s deep resentment of the West is rooted in this national myth .

Just as the Mongols were dealing with the challenge from Moscow , they faced a new threat from the Central Asian empire that was then emerging under the command of Timur , better known as Tamerlane . Timur’s army conquered Persia and the Caucasus and then went on to destroy the key trading bases of the Golden Horde , which began a slow but terminal decline . The weakening of the Horde , however , was due less to outside military threats than to the Black Death , which began on the Central Asian steppe in the mid – fourteenth century .

pandemic turned trade routes into plague routes , devastating the economy and killing perhaps half the population of the Golden Horde , which over the next century broke up into three khanates ( Kazan , Crimea , Astrakhan ) .

Muscovy remained a vassal of the khans until 1502 . Long before , however , it began to act as if it were an independent state .

Mongols stayed in Russia for more than three centuries . It was not until the 1550s that the khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan were finally defeated by Ivan IV ( the khanate of Crimea survived until 1783 ) . How much impact did these centuries have on the course of Russian history ? There

The Mongol period brought some positive advances for Russia . The postal system was the fastest in the world – a vast network of relay stations , each equipped with teams of fresh horses capable of carrying officials to all corners of the Mongol Empire at unheard – of speeds . It became the basis of the Muscovite system , which so impressed foreigners . Sigismund

The nineteenth – century socialist Alexander Herzen compared the repressive Nicholas I ( who reigned from 1825 to 1855 ) to ‘ Chingiz Khan with a telegraph ‘ . The Bolshevik Nikolai Bukharin said that Stalin was like ‘ Chingiz Khan with a telephone ‘ .

The most senior boyar clans – those who were closest through marriage or royal favour to the Moscow court – formed an oligarchic ruling class , which at times , when the grand prince was weak , might direct his government . But their wealth and power came from him . They kept them only for as long as they retained his protection . It was a system of dependency upon the ruler that has lasted to this day . Putin’s oligarchs are totally dependent on his will .

To some extent this greater freedom from the Mongol influence set the lands of Kiev on a different historical trajectory from Muscovy . The Kievan lands were more oriented to the West , less exposed to the institutions of patrimonial autocracy .

The dual nature of the Christian ruler – fallible in his humanity but divine in his princely functions – was a common notion in Europe . 4 The

By the 1530s the idea had been fleshed out in church tracts and legendary tales into what would later become known as the ‘ Third Rome doctrine ‘ .

year . Moscow itself had a population of perhaps 100,000 people by the early sixteenth century , almost twice as many as London .

Its vast complex of palaces and churches was constructed largely by Italians . The Hall of Facets ( the tsar’s palace ) was the work of the Venetian architects Marco Ruffo and Pietro Antonio Solari , who built the Kremlin’s walls in the style of the Sforza castle in Milan . Aristotele Fioravanti was responsible for the newly rebuilt Dormition Cathedral ( 1475 – 9 ) and Alevise Novi for the Archangel Cathedral , completed twenty years later . Over centuries many of the Kremlin’s buildings became Russified – Russian architectural elements and ornaments were gradually added – so that today visitors will not easily recognise its Italianate character . There

‘ All the people consider themselves to be the slaves of their Tsar , ‘ remarked Herberstein , who thought that ‘ in the sway which he holds over his people , he surpasses the monarchs of the whole world ‘ . 8 Ivan referred to his servitors as ‘ slaves ‘ ( kholopy ) . Protocol required every boyar , even members of the princely clans , to refer to themselves as ‘ your slave ‘ when addressing him – a ritual reminiscent of the servility displayed by the Mongols to their khans . This subservience was fundamental to the patrimonial autocracy that distinguished Russia from the European monarchies .

As this service class increased in size , the pressure on the state to find more land for it intensified . This became a major driving force of Russia’s territorial expansion – the conquest of new lands for the military servitors .

One result of the pomeste system was the creation of a landowning service class with only weak ties to a particular community . The pomeshchiki were creatures of the state .

The persistence of autocracy in Russia is explained less by the state’s strength than by the weakness of society . There were few public institutions to resist the power of the monarchy . The landowning class was overly dependent on the tsar .

This imbalance – between a dominating state and a weak society

Between 1500 and the revolution of 1917 , the Russian Empire grew at an astonishing rate , 130 square kilometres on average every day . 10 From the nucleus of Muscovy it expanded into the world’s largest territorial empire . The history of Russia , as Kliuchevsky put it , is the ‘ history of a country that is colonizing itself ‘ . 11

The Cossacks ‘ name derived from the Turkic word qazaqi , meaning ‘ adventurers ‘ or ‘ vagrant soldiers ‘ who lived in freedom as bandits on the steppe . Many of the Cossacks were remnants of the Mongol army ( Tamerlane had started out as a qazaq ) . They were joined by Russians from the north who fled in growing numbers to the ‘ wild lands ‘ of the south because of the economic crises caused by wars , rising taxes and crop failures in the ‘ little ice age ‘ of the sixteenth century .

The iconography borrows from the Book of Revelation , in which Michael defeats Satan before the Apocalypse . Ivan appears as a new King David and the Russians as God’s Chosen People , the new Israelites , reinforcing Moscow’s mythic status and mission in the world as the Third Rome . 12

Russian folklore , the ‘ fool for the sake of Christ ‘ , or Holy Fool , held the status of a saint , though he acted more like a madman or a clown , dressed in bizarre clothes , with an iron cap or harness on his head and chains beneath his shirt , like the shamans of Asia . He wandered as a poor man round the countryside , living off the alms of villagers , who found portents in his strange riddles and believed in his supernatural powers of divination and healing . Unafraid to speak the truth to the rich and powerful , he was frequently received by the nobility and became a common presence at the court . Ivan enjoyed the company of Holy Fools .

Instead he licensed private entrepreneurs to settle on the land , allowing them to exploit it for their own economic purposes and defend themselves with mercenary troops , usually Cossacks . The Stroganovs were the first big beneficiaries of this colonial policy . A wealthy merchant family with interests in saltworks and mining , in 1558 they leased vast tracts of land on the Kama River between Kazan and Perm . Their

Ivan became ‘ the Terrible ‘ – in the sense we understand today – only in the eighteenth century . The epithet ( grozny ) was first applied to him in the early seventeenth century , when a rich folklore about the tsar was just developing . At that time the meaning of the word was closer to the sense of awe – inspiring and formidable rather than cruel or harsh – so basically positive . In

They dressed in long black cloaks like a monk’s habit and rode around the country on black horses with dogs ‘ heads and brooms attached to their bridles – symbols of their mission to hunt out the tsar’s enemies and sweep them from the land . 15

The horror of the scene was captured by Repin in his 1885 painting Ivan the Terrible and his Son Ivan on 16 November 1581 , in which Ivan is shown consumed by remorse .

He was particularly angered by the film’s depiction of the oprichniki who , he said , appeared as ‘ the worst kind of filth , degenerates , something like the Ku Klux Klan ‘ , no doubt fearing that the viewing public would see in them a reference to his own political police .

The crucial factor in the tsar’s authority – his godlike personality projected through the myth of the holy tsar – could thus be turned against him if his actions did not meet the people’s expectations of his sacred cult .

There were dozens of ‘ pretender tsars ‘ ( samozvantsy ) who stirred the people to revolt by claiming they were the true tsar , the deliverer of God’s justice . At least twenty – three of these pretenders have been documented before 1700 , and there would be over forty in the eighteenth century .

The only way the Russians could legitimise rebellion was in the name of the true tsar . No other concept of the state – neither the idea of the public good nor the commonwealth – carried any force in the peasant mind .

historiography as the first peasant revolutionary . In fact he was a small – scale landowner and military servitor who , like so many of his kind , had fallen on hard times and run away to join the Cossacks , living as a bandit on the steppe .

Petitioning the tsar had a long tradition in Russia . It continued through the Soviet period when millions of people wrote to Stalin for his help against the abuses of his officials , and can still be seen in Putin’s annual TV programme Direct Line when viewers call in with their questions for the president .

The new Law Code extended their collective duty to mutual surveillance and denunciation of sedition to the state .

In one section worthy of the Stalinist regime , the code stated that the families of ‘ traitors ‘ , even children , were liable to execution if they failed to denounce their seditious relatives . Included in such crimes were expressions of intent to rebel against the tsar or public statements against him . The practice of informing became deeply rooted in society . By the late nineteenth century it was an effective tool of the police .

The Law Code divided the population into legally defined classes , known as estates ( sosloviia ) , strictly ordered in a hierarchy according to their service to the state . Each class was closed and self – contained . The service nobles , townsmen , clergy and peasants could neither leave their class nor hope their children would .

The social mobility that made Western societies so dynamic in the early modern age was basically absent in Russia . The town population in Russia was permanently fixed .

They sold themselves as slaves to the richer servicemen , which meant fighting in their place . The struggling pomeshchiki begged the tsar to support them . They wanted stricter laws to bind the peasants to their land . The result of their pleas was the institution of serfdom under the provisions of the new Law Code .

Stepan Razin was a Cossack from an area of the Don overrun by peasant fugitives . The migrants were ready to become ‘ Cossacks ‘ , to live a life of freedom , without masters or taxes .

Around 60,000 Jews were killed in 1648 alone – a level of killing that would not be equalled until the pogroms of the Russian Civil War .

In 1686 , Russia signed a Treaty of Eternal Peace with the Polish – Lithuanian Commonwealth .

Publishing was also controlled by the Church . Russia was the only country in Europe without private publishers , printed news sheets or journals , printed plays or poetry . When Peter the Great came to the throne , in 1682 , no more than three books of a non – religious nature had been published by the Moscow press since its establishment in the 1560s .

where priests were trained in Latin as well as Slavonic .

Elsewhere , as the soldiers of the tsar approached , the Old Believers shut themselves inside their wooden churches and burned themselves to death to avoid submitting to the Antichrist .

They continued to follow the teachings of Avvakum , disseminated from his place of enforced exile in the Arctic fort of Pustozersk , where in 1680 he was burned at the stake .

Until the eighteenth century , the Russians followed the Byzantine custom of counting years from the creation of the world , an event which they believed had occurred 5,508 years before the birth of Christ . But in December 1699 Tsar Peter decreed a calendar reform . Henceforth years were to be numbered from Christ’s birth , ‘ in the manner of European Christian nations ‘ , beginning on 1 January 1700 ( 7209 in the old system ) .

Peter was a man in a hurry . Almost seven feet in height ,

He set up a new system of conscription , unparalleled in Europe , in which units of twenty peasant households were each collectively responsible for sending one man for life into the army every year , and even more at times of war . This sweeping militarisation of society produced the largest standing army in the world – some 300,000 troops by Peter’s death , in 1725 , and 2 million men by 1801.4 No other state could mobilise so many men .

It was said that Peter made his city in the sky and then lowered it , like a giant model , to the ground . Here was a new imperial capital without roots in Russian soil .

He gave himself the Latin title ‘ Imperator ‘ and had his image cast on a new rouble coin , with laurel wreath and armour , in imitation of Caesar . It was a symbolic break from Muscovy , with its Byzantine mythology , in which the tsar had been portrayed as a divine agent and defender of the faith . Now he appeared in armour with a Western crown and cloak and imperial regalia

He made state service compulsory for the nobility , whose status was defined by the seniority of their office rather than by birth .

The Table of Ranks , introduced in 1722 , established fourteen ranks or categories of state service , in which hereditary nobility was conferred on office – holders in the top eight ranks . Commoners could enter at the bottom rank and earn noble titles by working up to the eighth rank ( collegiate assessor in the government , major in the army or third captain in the navy ) . This ordering of the nobles by their service to the state lasted until 1917 . It had a deep effect on the nobles ‘ way of life , further weakening their attachment to the land . Because promotion was normally by seniority , the system rewarded time – servers and encouraged bureaucratic mediocrity .

From the middle of the eighteenth century we can see the emergence of a new national consciousness which found its first expression in an anti – Western ideology . It was based on the defence of Russian customs and morals against the corrupting impact of the West – a trope of the later Slavophiles .

Whether Saltykov was Paul’s father remains unknown , but Catherine’s memoirs hinted that he was , much to the horror of her nineteenth – century descendants , who censored any mention of his name .

Peter meekly surrendered ( on hearing of his overthrow , Frederick the Great said that he had ‘ let himself be driven from the throne as a child is sent to bed ‘ ) . Peter was exiled to one of his estates near St Petersburg , where he was murdered three weeks later by Orlov . It was announced that he had died of ‘ haemorrhoidal colic ‘ – prompting one French wit to note that haemorrhoids must be very dangerous in Russia . 18

A follower of the Enlightenment , she emphasised the need to educate the nobles as agents of enlightened government . She wanted to create a noble class that would serve the public good , not by compulsion but from a sense of obligation to society ( noblesse oblige ) .

What she meant by this simple statement was that , on account of its European character , Russia had a natural mastery over all the peoples of Asia .

Montesquieu . Although she disputed Montesquieu’s conception of Russia as an oriental despotism , she accepted his idea that laws should be consistent with the spirit of a nation shaped by climate and geography .

‘ You were right in not wanting to be counted among the philosophes , ‘ she wrote to Grimm at the height of the Jacobin terror in 1794 , ‘ for experience has shown that all of that leads to ruin ; no matter what they say or do , the world will never cease to need authority . It is better to endure the tyranny of one man than the insanity of the multitude . ‘

On his accession to the throne Paul restored the principle of primogeniture to the law of succession , effectively ensuring that his mother would be the last female ruler of Russia .

Appalled by his tyranny , a small group of drunken officers broke into the Mikhailovsky Palace and strangled Paul to death on the night of 23 – 24 March 1801 . The officers were acting on the orders of a court conspiracy with close links to Alexander , son of Paul and heir to the throne , who had set the date for the killing .

Barely 10 per cent of the invasion force would make it back

Alexander was convinced that all these groups were connected to a secret international Bonapartist organisation . He urged the Holy Alliance to root them out and destroy them before they spread to Poland and Russia . At

The officers began to organise themselves in secret circles of conspirators , like those in Spain and Italy , often building on the networks of the Freemasons , banned by Alexander in 1822 , to which most of them belonged . All were in favour of a liberal constitution and the abolition of serfdom , but they were divided over how to bring this end about . Some wanted to wait for the tsar to die , whereupon they would refuse to swear allegiance to his successor unless reforms were introduced .

His younger brother Nicholas did not announce his decision to take the crown instead until 12 December . Pestel resolved to seize the moment for revolt and hurried to St Petersburg to organise it with his fellow officers – the Decembrists as they would be known .

They conceived of the uprising as a military putsch , instigated by orders issued by the officers , without even thinking whether the soldiers ( who showed no inclination for an armed revolt ) would go along with them . In the end , the Decembrist leaders rallied the support of 3,000 troops in Petersburg – far fewer than the hoped – for 20,000 men , but still enough perhaps to bring about a change of government if well organised and resolute . But that they were not .

Pestel and four others were hanged in the courtyard of the fortress , even though officially the death penalty had been abolished in Russia . When the five were strung up on the gallows and the floor traps were released , three of the condemned proved too heavy for their ropes and , still alive , fell into the ditch . ‘ What a wretched country ! ‘ cried one of them . ‘ They don’t even know how to hang properly . ‘ 6

Known as ‘ official nationality ‘ , this new ideology was based on the old myth that the Russians were distinguished from the Europeans by the strength of their devotion to the Church and tsar and by their capacity for sacrifice in the service of a higher patriotic goal .

The Slavophiles were opposed to the Westernising reforms begun by Peter the Great . They feared that these changes , imposed by a state that was ‘ foreign ‘ to the peasants , would result in the loss of Russia’s national character , its native customs and traditions . The

‘ Intelligentsia ‘ is in origin a Russian word .

Published in the same year as Uncle Tom’s Cabin , the Sketches had as big an impact in swaying Russian views against serfdom as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book had on the anti – slavery movement in America .

The humiliation was to leave a deep and lasting sense of resentment towards the West . It continues to this day . All Putin’s talk of Western ‘ double standards ‘ and ‘ hypocrisy ‘ , of Western ‘ Russophobia ‘ and ‘ disrespect ‘ for Russia , goes back to this history . In

The war had brutally exposed the country’s many weaknesses : the corruption and incompetence of the command ; the technological backwardness of the army and navy ; the poor roads and lack of railways that accounted for the chronic problems of supply ; the poverty of the army’s serf conscripts ; the inability of the economy to sustain a state of war against the industrial powers ; the weakness of the country’s finances ; and the failures of autocracy . Critics focused on the tsar , whose arrogant and wilful policies , as they now seemed , had led the country to defeat and sacrificed so many lives . Even within the governing elite the bankruptcy of the Nicholaevan system was coming to be recognised .

‘ My God , so many victims , ‘ wrote the tsarist censor Alexander Nikitenko in his diary . ‘ All at the behest of a mad will , drunk with absolute power … We have been waging war not for two years , but for thirty , maintaining an army of a million men and constantly threatening Europe . What was the point of it all ? ‘

They found one , a semiliterate peasant and Old Believer called Andrei Petrov . After studying the proclamation for three days , he managed to interpret the statutes in a way that told the peasants what they had wanted to hear all along .

The commune emerged from the Emancipation as the basic unit of administration in the countryside . The mir , as it was called , a word that also means ‘ world ‘ and ‘ universe ‘ , regulated every aspect of the peasants ‘ lives : it decided the rotation of the crops ( the open – field system of strip farming necessitated uniformity ) ; took care of the woods and pasture lands ; saw to the repair of roads and bridges ; established welfare schemes for widows and the poor ; organised the payment of redemption dues and taxes ; fulfilled the conscription of soldiers ; maintained public order ; and enforced justice through customary law .

Second was the labour principle – basically a peasant version of the labour theory of value . The peasants attached rights to labour on the land . They believed in a sacred link between the two . The land belonged to God . It could not be owned by anyone . But every peasant family should have the right to feed itself from its own labour on the land . On this principle the landowners did not fairly own their land , and the hungry peasants were fully justified in claiming their right to farm it . A constant battle was thus fought between the state’s written law , framed to defend property , and the peasants ‘ customary law , which they used to defend their transgressions of the landowners ‘ property . The

The practice of communal repartitioning encouraged the peasants to have bigger families – the main criterion for receiving land . The birth rate in Russia was nearly twice the European average in the latter nineteenth century . The rapid growth of the peasant population ( from 50 to 79 millions between 1861 and 1897 ) resulted in a worsening land shortage . By the turn of the century 7 per cent of the peasant households in the central zone had no land at all , while one in five had less than one hectare . Although

Lacking the capital to modernise their farms , the easiest way the peasants had to feed themselves was by ploughing more land at the expense of fallow and other pasture lands . But this made the situation worse . It meant reducing livestock herds ( the main source of fertiliser ) and the exhaustion of the soil . By 1900 , one in three peasant households did not have a horse . 6 To cultivate

The common image of the tsarist regime as omnipresent and all – powerful was largely an invention of the revolutionaries , who spent their lives in fear of it , living in the underground . The reality was different . For every 1,000 inhabitants of the Russian Empire there were only four state officials at the turn of the twentieth century , compared with 7.3 in England and Wales , 12.6 in Germany and 17.6 in France . For a rural population of 100 million people , Russia in 1900 had no more than 1,852 police sergeants and 6,874 police constables . The average constable was responsible for policing 50,000 people in dozens of settlements scattered across 5,000 square kilometres . 10

After the failure of the ‘ Going to the people ‘ , as the events of 1874 were known , Tkachev argued that such methods were too slow . Before a social revolution could be organised a class of richer peasants , whose interests lay in the status quo , would appear as a result of capitalist development and assert its domination in the countryside . Tkachev argued for a putsch by a disciplined vanguard , which would set up a dictatorship before engineering the creation of a socialist society by waging civil war against the rich . He claimed the time was ripe to carry out this coup , since as yet there was no major social force , just a weak landowning class , prepared to defend the monarchy . Delay would be fatal , Tkachev argued , because soon there would be such a force , a bourgeoisie , supported by the ‘ petty – bourgeois ‘ peasantry , which would be formed by the new market forces in Russia .

It is hard to think of a more momentous turning – point in Russian history . On the day the tsar was killed , 1 March , he had agreed to a reform that would include elected representatives from the zemstvos and town councils in a new consultative assembly . Although it was a limited reform , by no means implying the creation of a constitutional monarchy , it showed that Alexander was prepared to involve the public in the work of government . On 8 March , the proposal was rejected by his son and heir , Alexander III , in a meeting of grand dukes and ministers . The most reactionary and influential critic , Konstantin Pobedonostsev , procurator of the Holy Synod , warned that accepting the reform would represent a first decisive step on the road to constitutional government . At this time of crisis , he maintained , Russia was in need not of a ‘ talking shop ‘ but of firm actions by the government . From that point , the new tsar , who would rule from 1881 to 1894 , pursued an unbending course of political reaction to restore the autocratic principle .

Until 1904 , they could even have the peasants flogged for minor crimes . The impact of such corporal punishments – decades after the Emancipation – cannot be overstressed . It made it clear to the peasantry that violence was the basis of state power – and that violence was the only way to remove it .

Russian was made compulsory in schools and public offices . Polish students at Warsaw University had to suffer the indignity of studying their national literature in Russian translation .

During the 1907 cholera epidemic in the Kiev area , doctors were forbidden to publish warnings not to drink the water in Ukrainian . But the peasants could not read the Russian signs , and many died as a result .

The last two tsars encouraged this . Nicholas II , in particular , saw the pogroms as an act of loyalty by the ‘ good and simple Russian folk ‘ . He became a patron of the Union of the Russian People , formed in 1905 , which instigated more than one pogrom . Little wonder , then , that Jews were prominent in the revolutionary underground . The Marxist movement , in particular , was attractive to the Jews . The

Whereas Populism had proposed to build a socialism based on peasant Russia , the land of pogroms , Marxism was based on a modern Western vision of Russia . It promised to assimilate the Jews into a movement of universal human liberation based on internationalism .

Millions of peasants came into the towns , some drawn by ambition , others forced to leave the countryside because of overpopulation on the land . Between 1861 and 1914 the empire’s urban population grew from 7 to 28 million people . First came the young men , then the married men , then unmarried girls , who worked mainly in domestic service , and finally the married women with children

Contrary to the Soviet myth , in which Lenin was a Marxist theorist from his infancy , he came late to politics . He was born in 1870 into a respectable and prosperous family in Simbirsk , a typical provincial town on the Volga . His father was inspector of the Simbirsk district’s primary schools . In Lenin’s final year at secondary school , a middle – class gymnasium , he was highly praised by his headmaster , who by one of those strange historical ironies was the father of Alexander Kerensky , the prime minister Lenin would overthrow in October 1917 .